Rokeby Museum Distance Drawing Course — Week 1: Vision

WEEK 1 | WEEK 2 | WEEK 3 | WEEK 4 | WEEK 5 | WEEK 6

Inspired by Rachael Robinson Elmer (1878–1919) and taught by Courtney Clinton, Rokeby Artist in Residence

Dear Student,

My name is Courtney Clinton, I am a Montreal-based artist whose practice focuses on art history and drawing. This summer, I am the artist in residence at Rokeby Museum.

In fall 2019, I visited the Rokeby Museum as part of the Contemporary Art at Rokeby Artist Lab organized by curator Ric Kasini Kadour. In the museum’s archive of the family’s letters and artifacts, I discovered the original letters (dated 1891–1893) from a correspondence drawing course that one of the daughters, Rachael Robinson Elmer (1878–1919), took as an adolescent.

Rachael was part of four generations of Robinsons that made Rokeby their home. Rachael would eventually move to New York to study at the Art Students League and go on to be an important book illustrator — an esteemed position for artists of the day. In 1914, Rachael designed and published a series of watercolour postcards, Art Lover’s New York. This work garnered her national acclaim and is now part of the National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., collection.

Catherine Brooks, the Rokeby Director, and I agreed that exploring this correspondence course now, during the COVID-19 crisis, is a way to start a timely conversation around remote education. Despite the American-Canadian border closure, the museum is generously making their archives available to me through a digital collaboration between myself and Rokeby’s Education and Interpretation Fellow, Allison Gregory.

Each week I will share with you an exercise from the 1890s drawing course and together we will work through it using pictures demonstrating the lesson and written steps. We will also explore Rokeby’s collection of Rachael’s drawings and paintings, and talk about her journey to become a recognized 20th century illustrator. My collaboration with the Rokeby Museum, and this adventure with you, presents an opportunity to test and expand upon the possibilities of remote learning and remote collaboration. So let’s get started!

Note: As you work your way through this course, share your work! Be sure to tag @clinton.courtney and @rokebymuseum on Instagram and use the hashtags #RokebyDistanceDrawing and #DrawingWithRachael. Got a question for Courtney? Let us know in the comment section below!

Exploring the Museum’s Collection

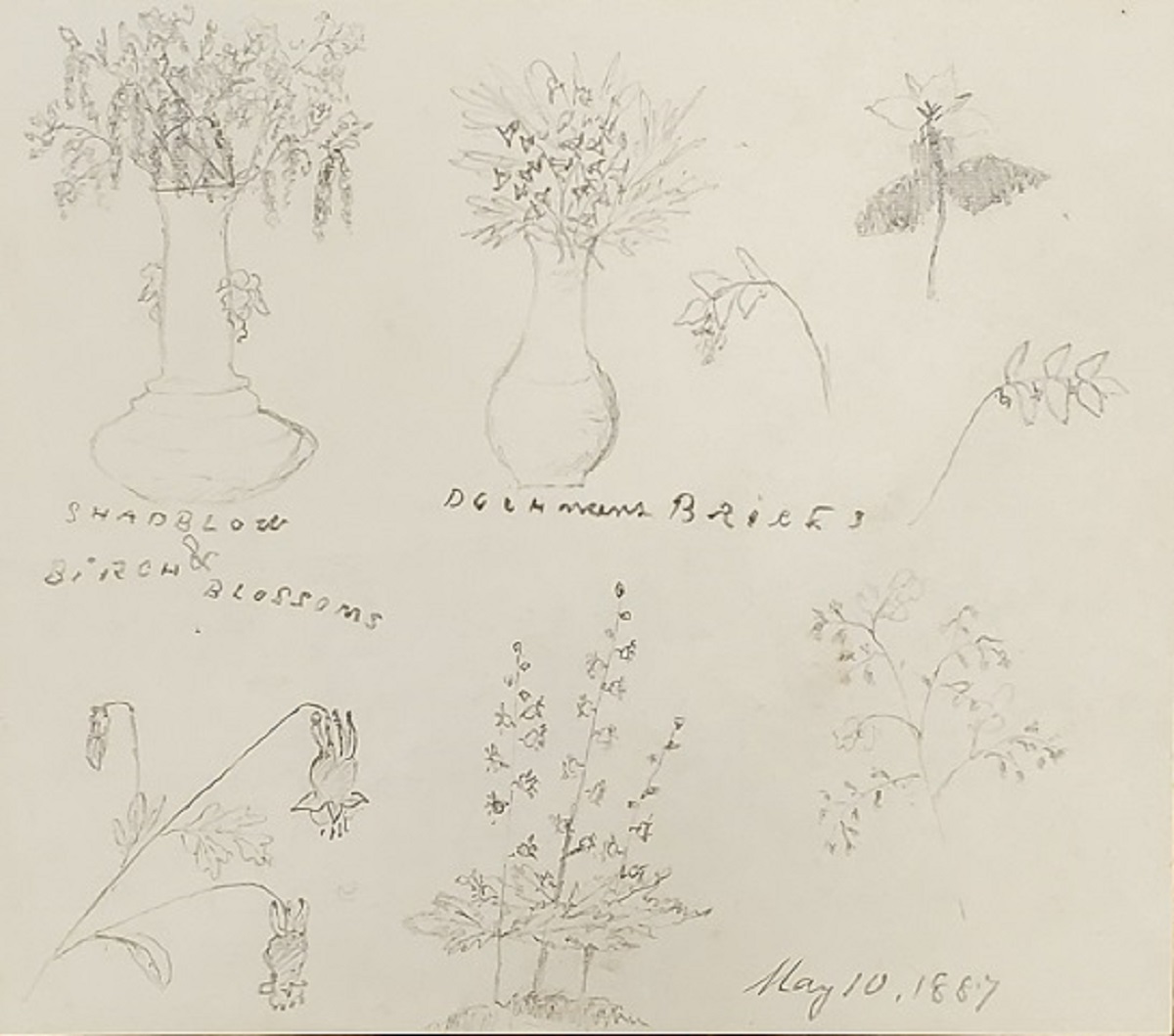

Botanical Workbooks

Before we look at the drawing course, let’s take a minute to get to know the young Rachael Robinson Elmer.

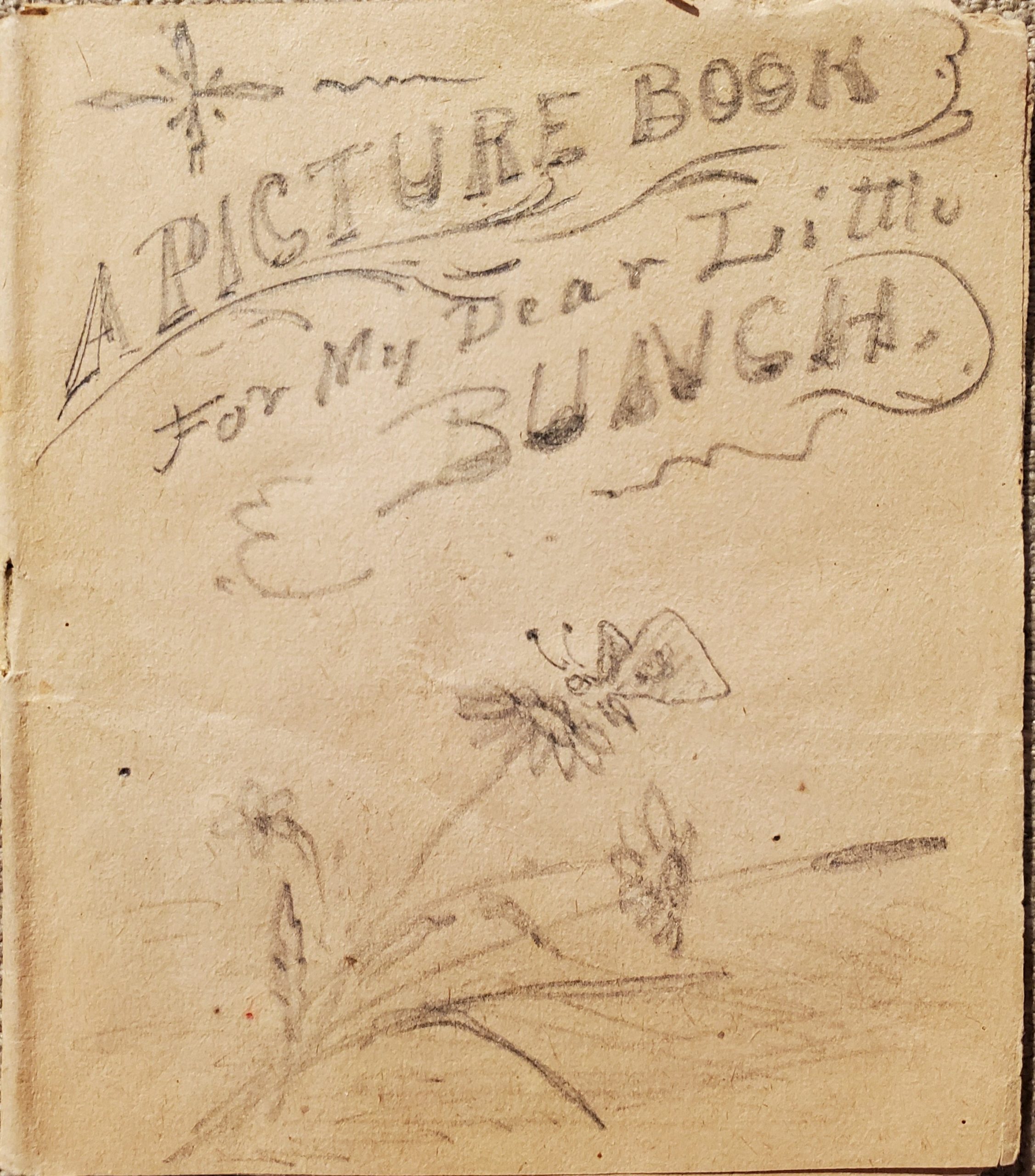

Rachael was the daughter of Rowland Evans Robinson (1833–1900) and Ann Stevens Robinson (1841–1920). She was born in 1878 and grew up on the Rokeby property. From a young age, Rachael grew up around art and nature. Her parents created small books for their little “Bunch” of animals and other things in nature. Her father had a deep appreciation for nature and, later, wrote about nature in books like In New England Fields and Woods with Sketches & Stories and Forest and Stream Fables.

Growing up in rural Vermont Rachael had few opportunities to study art. At 12 the Robinsons enrolled Rachael in the Chautauqua Society of Fine Arts correspondence drawing course. Rachael would study with the New York artist Ernest Knaufft (1864–1942) from 1891 to 1895 — first by correspondence and later at his studio in New York.

From the letters we know that her mother Ann wrote on Rachael’s behalf to her teacher Ernest Knaufft. Ann was a gifted artist. Her botanical and fruit paintings include great detail, showing a very careful eye and hand. We can imagine that as Rachael worked through the different exercises, her mom was at her side encouraging her through the work.

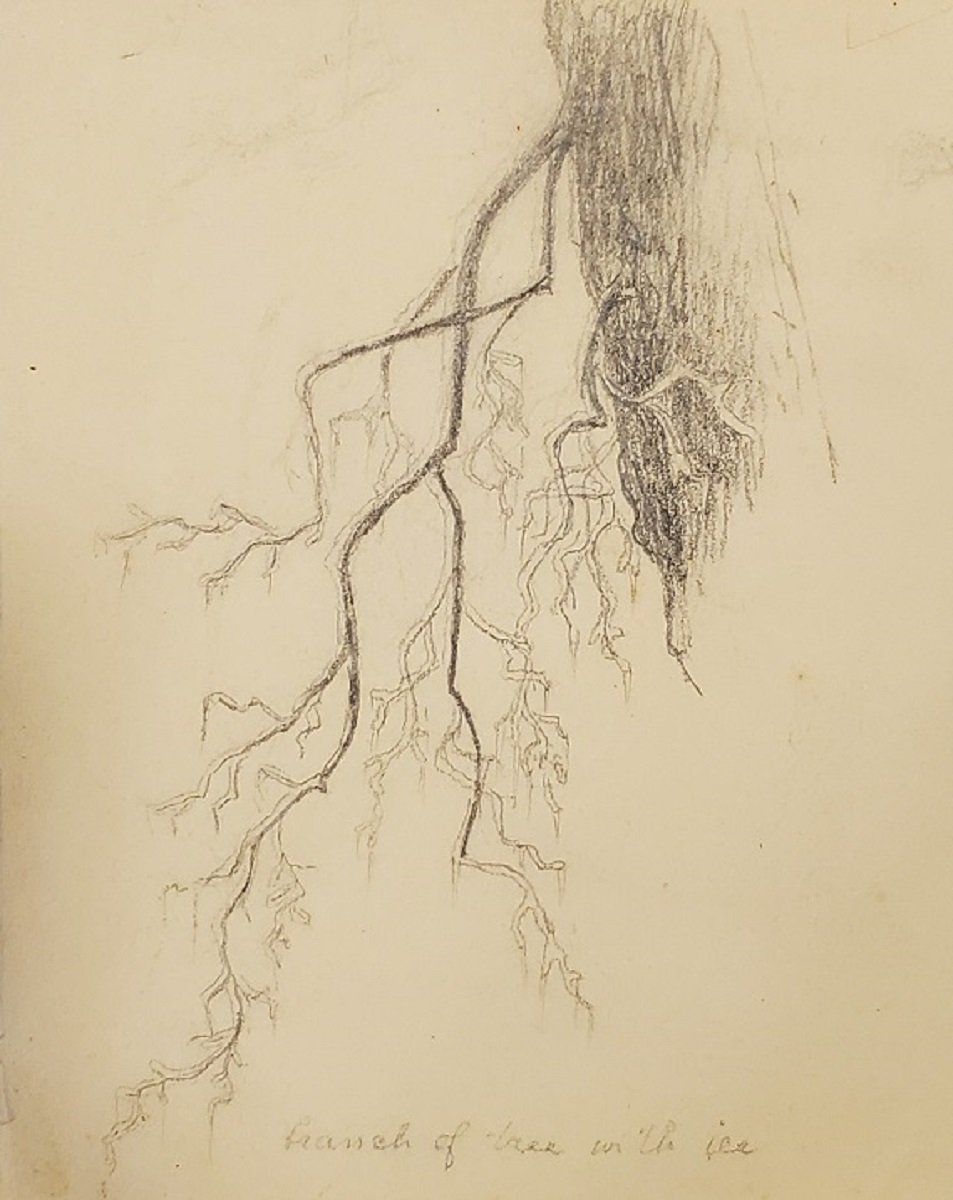

Ann also taught Rachael and her sister Molly how to make botanical studies from nature.Rokeby Museum has a beautiful collection of workbooks filled with flower drawings made by the three Robinson women.

Rachael’s Diary

Included in the museum’s archival material about Rachael is her diary from 1901 to 1902. When I first came across this material, I have to admit, I was excited to read the secret thoughts of a young Rachael. I imagined stories of heartache and retellings of epic fights with her sister Molly.

Instead, Rachael’s diary is filled with beautiful descriptions of her walks in nature.

Yesterday I was sketching in Mr. Macomber’s orchard. The pear trees were a little past fresh bloom, and the pale yellowish-green on the peeping leaves, gave to the mass of blossom a yellow tint. Their perfume made the air sickening. (May 18, 1902)

Rachael’s father Rowland became famous for his writing on nature and rural Vermont life. Perhaps Rachael was following her father’s example in her writing.

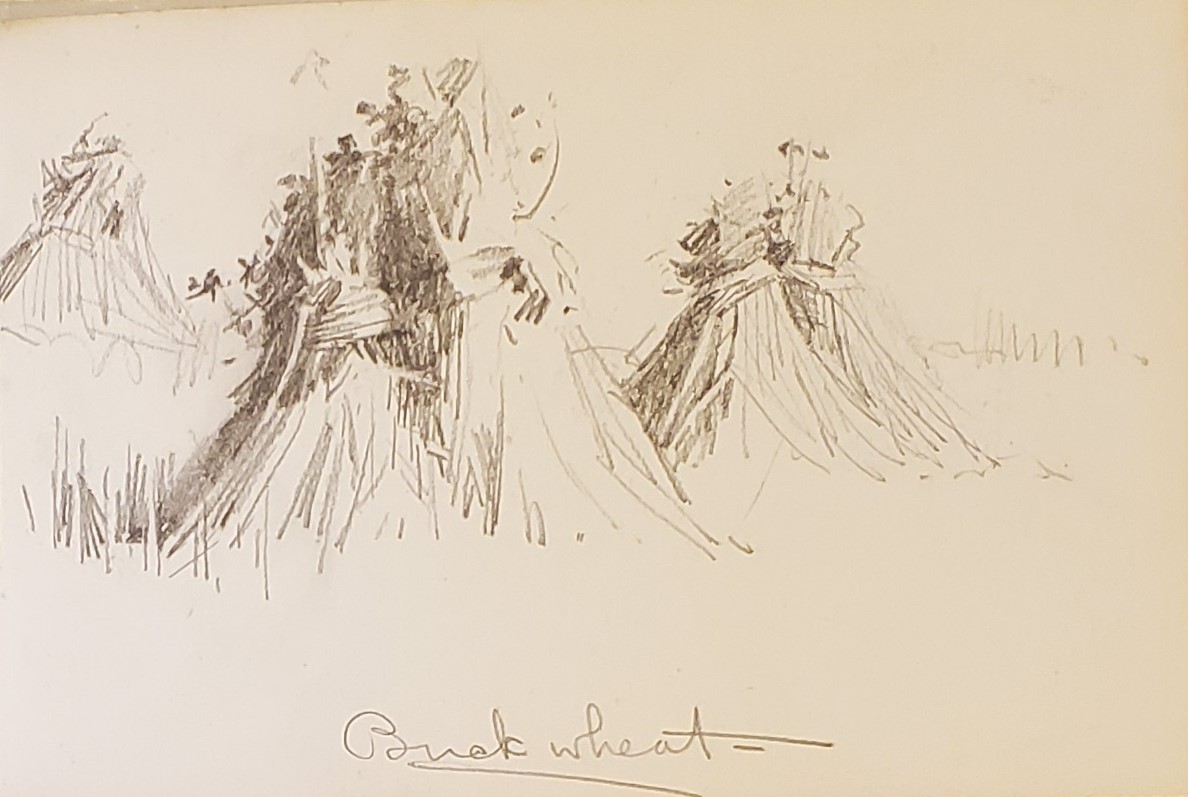

Often Rachael would write about and sketch the same spot.

A field of buckwheat in shock on the eastern slope of the hill, is dark red brown — the shocks I mean. (October 31, 1902)

In other entries, she goes beyond the material and considers the histories that the landscape evokes.

Asa Staples, an old friend who used to live in Monkton just East of Fuller Mountain says that my grandfather used to take runaway slaves up to the top of our mountain and show them a great pine stub on the pinnacle of Fuller Mountain to get their bearings to reach his fathers the next station. (April or early May 1902 (no date))

Beyond being poetic and a joy to read, Rachael’s diary gives us insight into her thinking as an artist. In her writing on nature she articulates how she breaks down elements into a series of colours and shapes.

A little plum tree was a perfect mass of bloom — each twig a thick stalk of white. It was like a Japanese picture against the delicate but intense blue of the sky. (May 18, 1902)

Drawing Exercise

Seeing Rachael’s drawings and writing side by side gives us a new way to think about the practice of drawing. In her sketchbooks, Rachael uses drawing to take visual notes. With her art, she is recording and testing her understanding of nature.

Five Botanical Drawings

For this week’s exercise I invite you to start a sketchbook practice. Over the next two weeks, go for walks with a sketch book and make small sketches of the different things that you see. Try to do five botanical sketches a week.

Don’t know where to start? Don’t worry, we are in this together! Below is a step by step guide to start your first sketchbook.

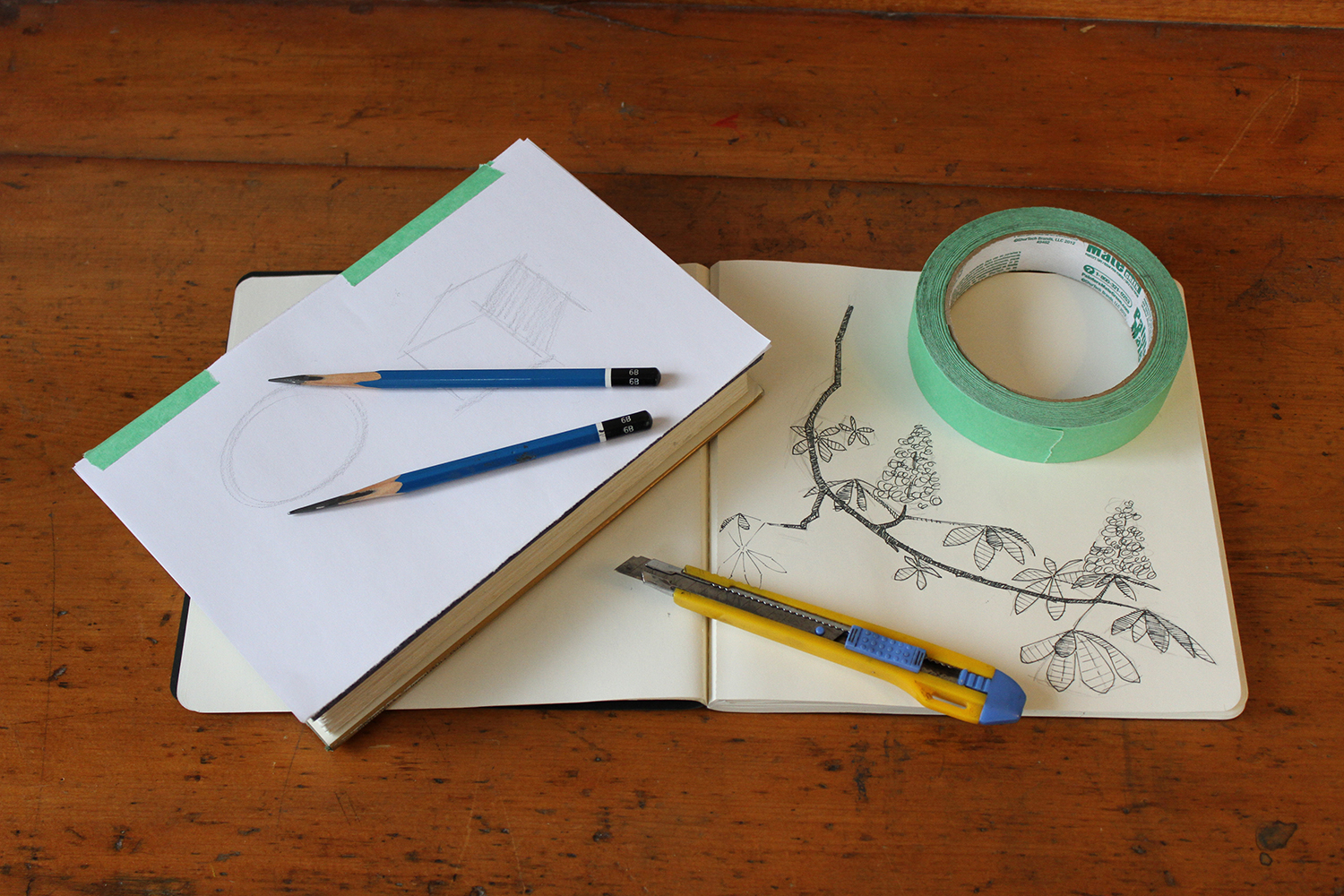

Sketchbook Kit

When we are working outside it is easier to keep things compact. You want something you can easily hold in one hand. I recommend a sketchbook approximately 5″ x 7″. If you don’t have a sketchbook, you can always tape a couple pieces of computer paper (cut in half) to the back of a hardcover book!

Pencil

In school we used what is called an HB pencil. The lead is hard and the pencil makes a light line when we press it onto the page. For quick sketch drawings, I recommend using a 6B pencil. These pencils are considered soft. By varying your pressure you can make both dark and light lines. If you can’t make it to an art store, you can always use any pencil lying around the house or from the pharmacy (though avoid mechanical!).

Sharpening your pencil

It is very important to keep your pencil sharp while you draw. You’re welcome to use a traditional pencil sharpener, but back when Rachael was learning to draw, artists would use a knife to sharpen their pencil. Like Rachael, I use an exacto knife to sharpen my pencil. This method keeps the lead sharper for longer — plus it makes you feel like an artist.

Eraser

Instead of using an eraser, play around with the pressure of your 6B pencil lines. Make a light rough of your sketch. Once you are happy with placement, add a little pressure and emphasize the final lines of your drawing.

I challenge you to leave your eraser at home. I want you to see what it feels like to push through your “mistakes” and finish each drawing. You’ll see, it feels pretty good.

Investigation Through Drawing

For this exercise I chose to study lilac trees. Every June, Montreal is covered with the most beautiful blooming lilac trees. The city smells wonderful and you see light purples and pinks in all the parks and gardens.

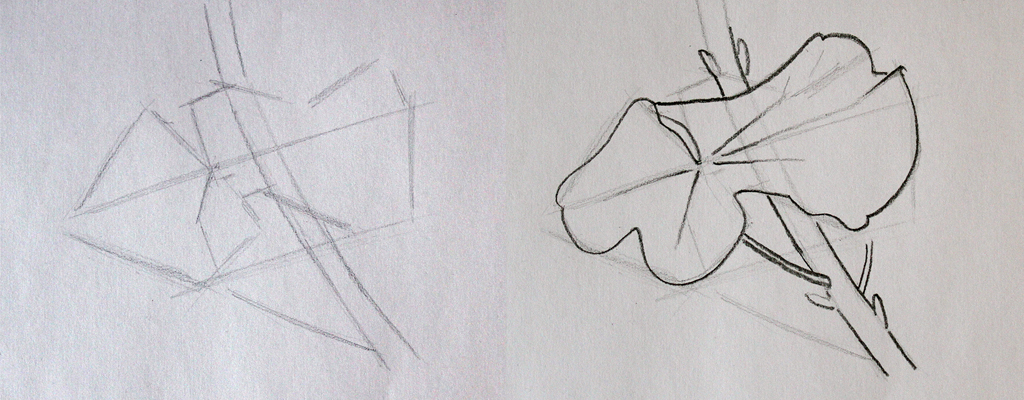

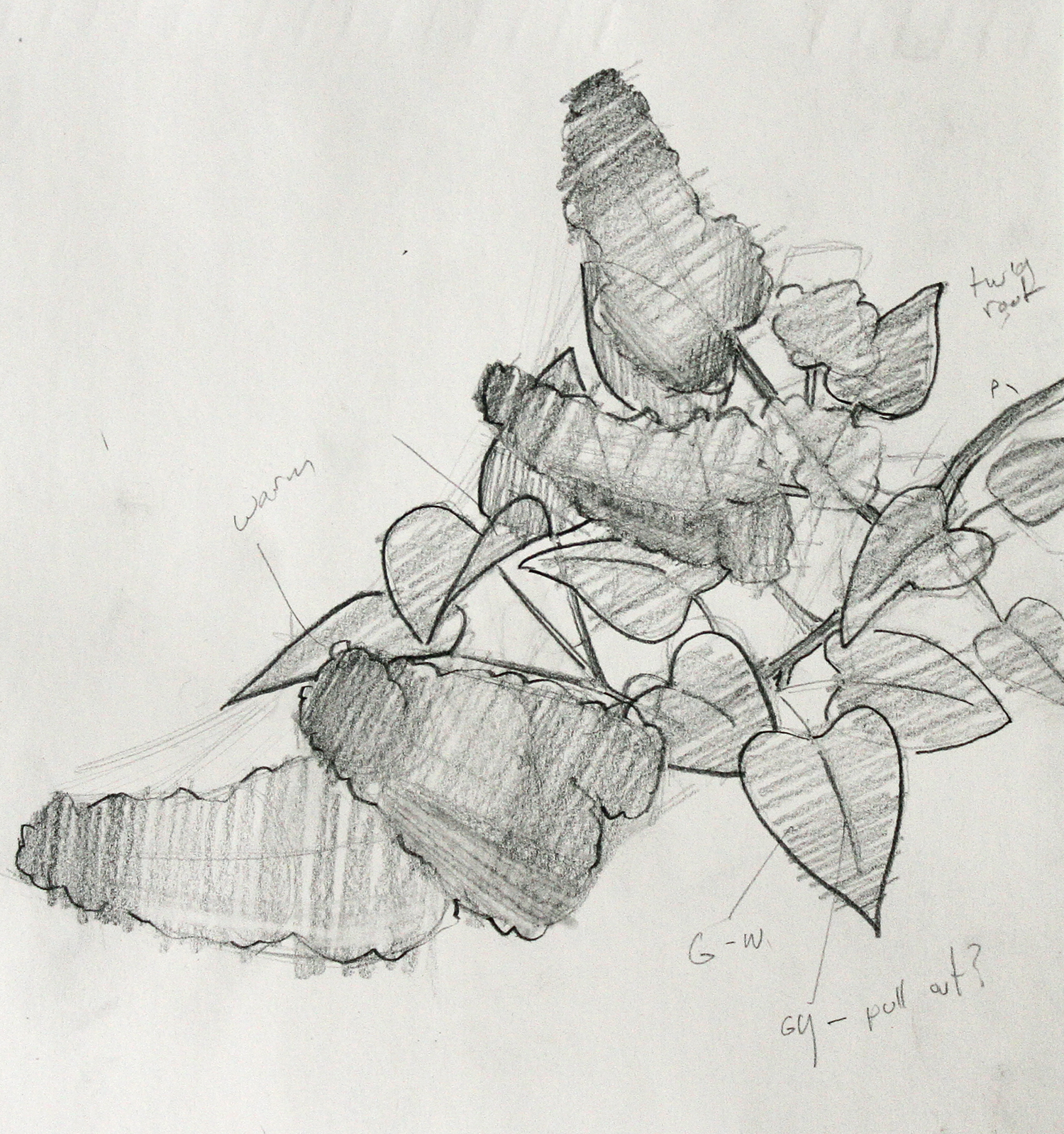

I kept my same subject (lilac blossoms) for each sketch but I varied my angle and compositions.

Back in my studio, I decided I would take one of my sketches and turn it into a more finished drawing. As I started to analyse my drawings, I realised there was some critical information missing. Looking at my drawings, away from the actual lilac trees, it wasn’t clear how the leaves or the blossoms were attached to the branches of the tree.

As an artist, if I don’t understand what I am drawing then I can’t expect my audience to understand my image. I decided that before I moved on to making a final drawing, I had to go back out into the field to get more information.

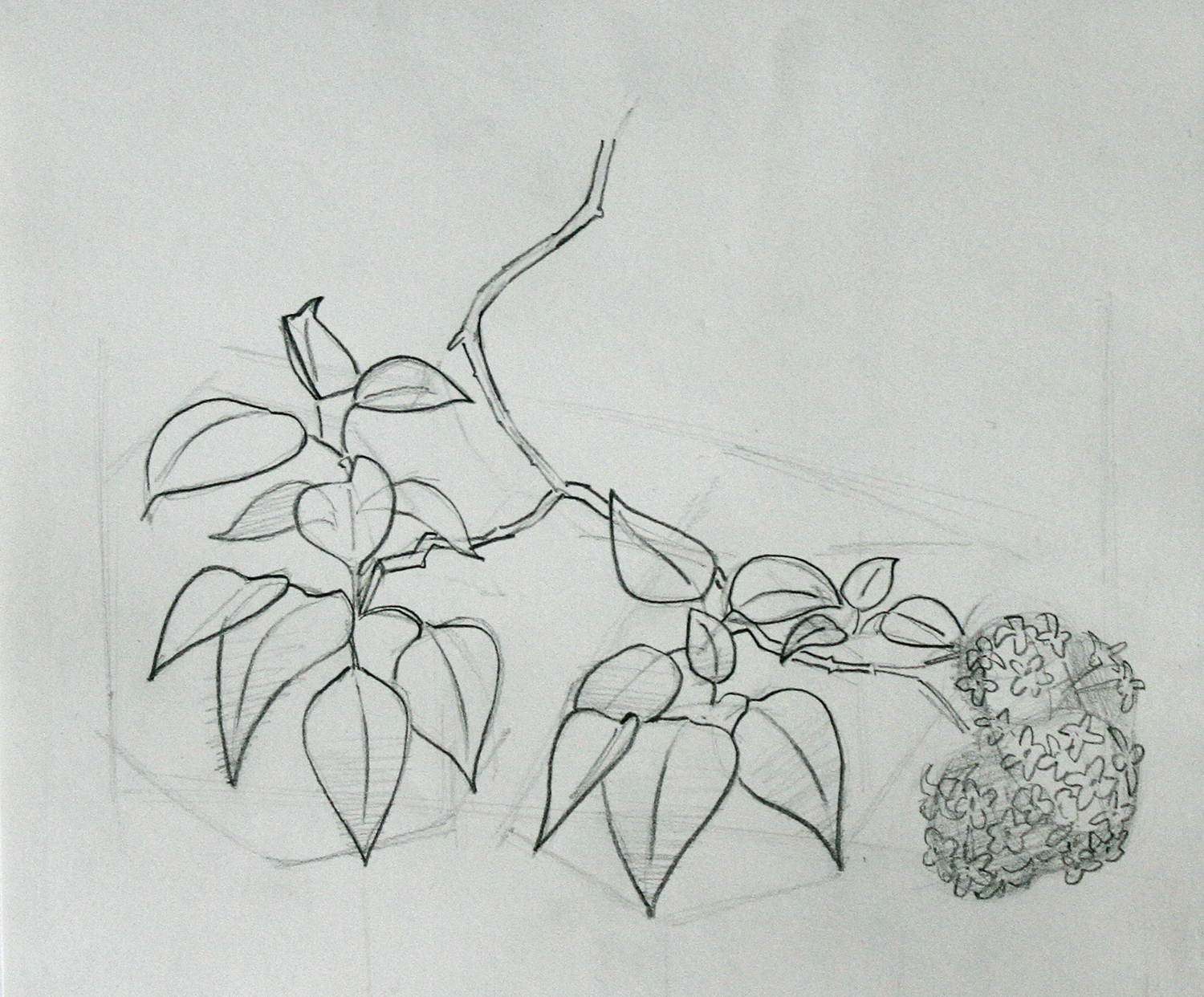

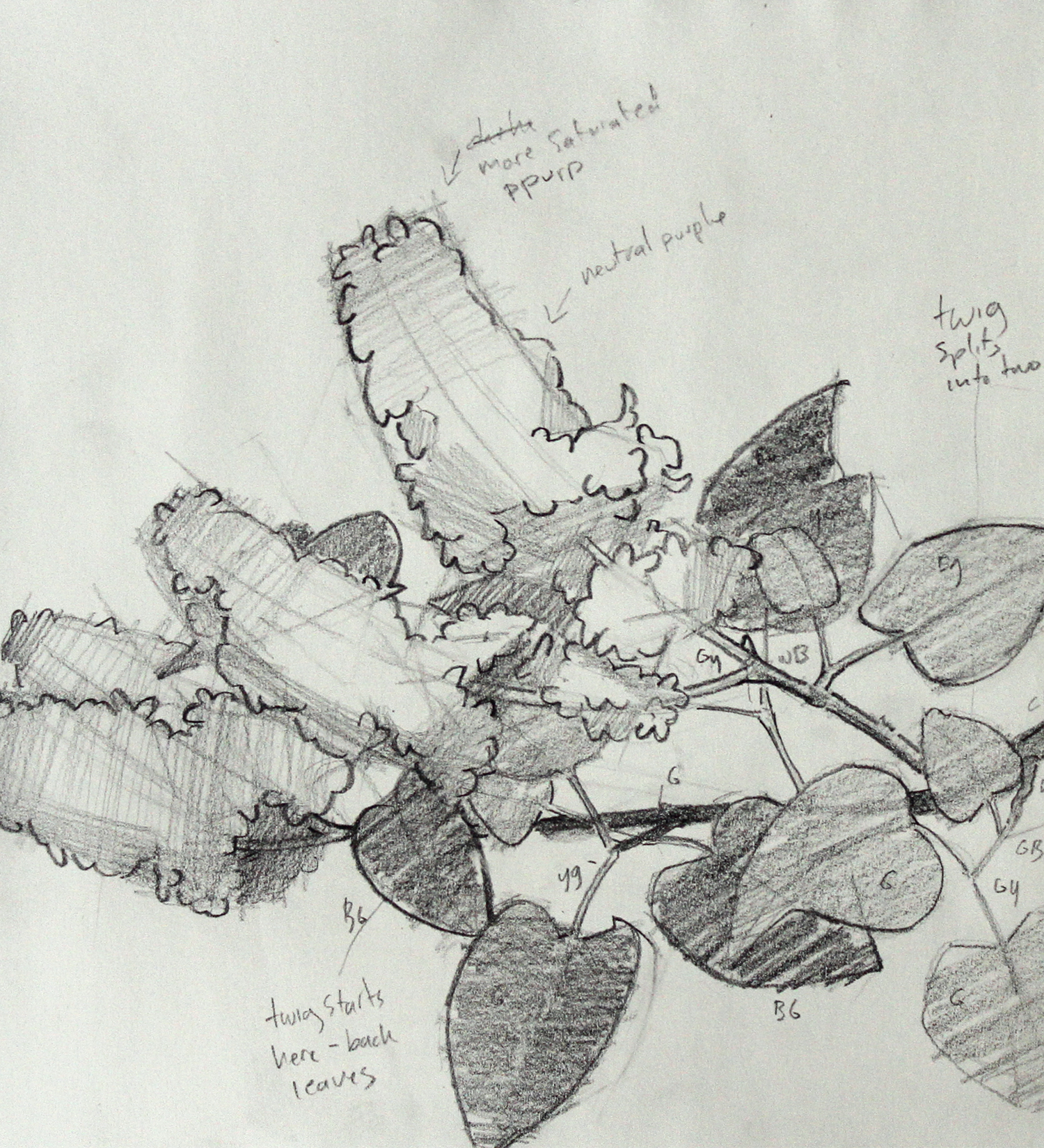

Back in the field, I made sure to connect every leaf to a twig and that twig back to the main branch. This meant moving around to look at the lilac tree from different angles. It also meant gently lifting leaves that were blocking my view. I went so far as to make little notes on the page of where different twigs started (when the spot was covered by a leaf).

As an artist you can’t be afraid to change angles and poke and prod. This is why we work from a live subject. If you work from a photograph you only get one angle and you can’t touch your subject. But when we work from life we can really get in there and do some in depth investigation.

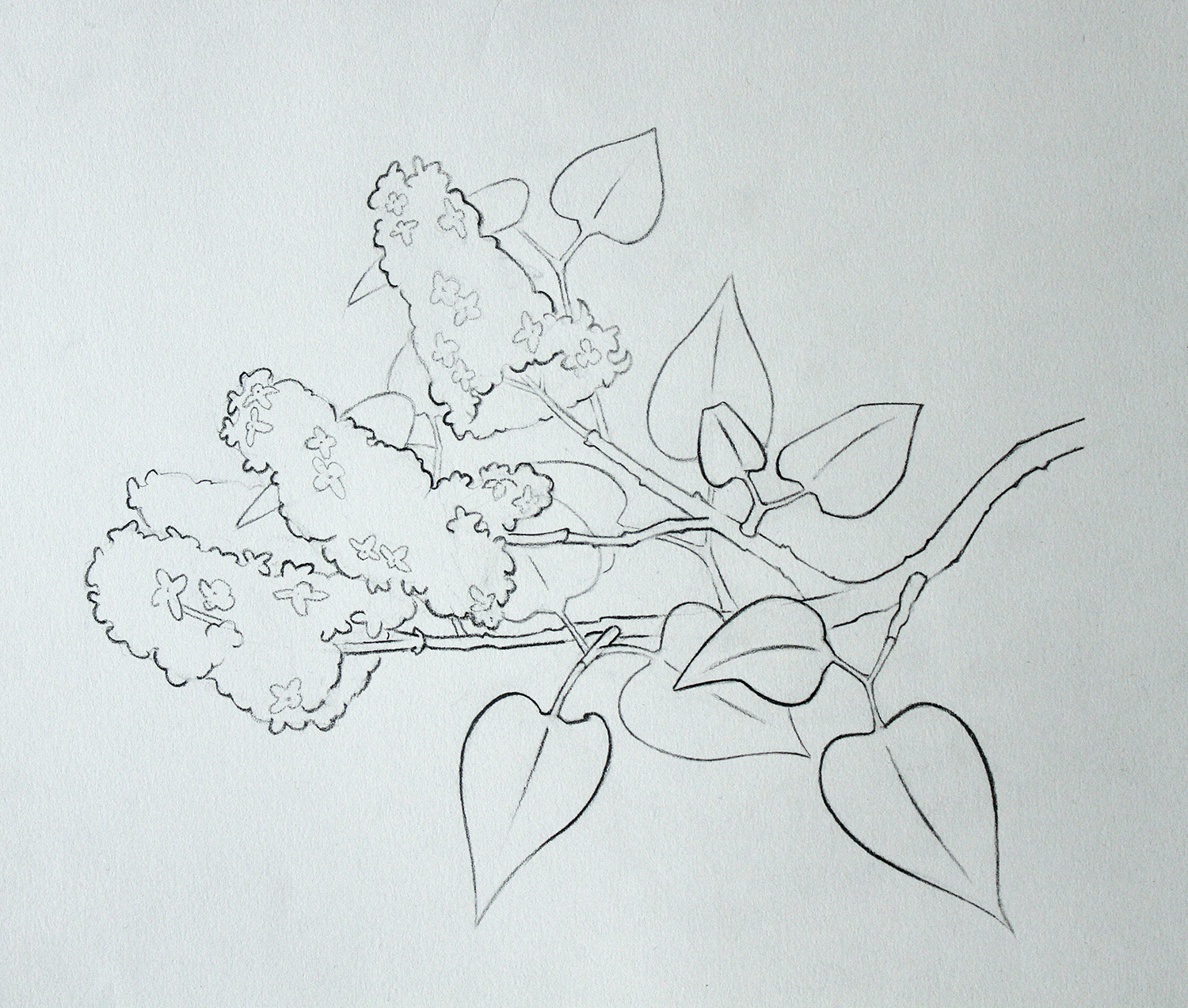

Energized by my research, I did a second drawing of the same bunch of flowers from a different angle. Instead of drawing them from a side view I moved to a frontal position. From this angle it was harder to see all the small twigs that are home to all those leaves. I used the information I gathered in my first drawing to help guide me. As artists, it is our job to communicate not only what the eye can see, but also the hidden structures that support and inform what we are seeing — it’s a heck of a job, but does wonders for your appreciation of details!

Final Drawing

Sketch drawings and final drawings are two very different kinds of drawing. When I make a sketch, I’m really thinking about my subject. I don’t worry about being messy or about mistakes.

Back in the studio, is when I start to think in more creative terms. I already have all this great research from my sketches, so I don’t have to worry about the mechanics of my subject. Now, I can concentrate on how to use art elements, like line, to make an interesting and artistic image.

Using my 6B pencil I experimented with line pressure. I kept the lines for the front leaves and branch nice and dark. For the leaves in the back I used a lighter line. This contrast helps to communicate a sense of space between the front and back of the image.

Signing Off

Often we assume that because we have always been surrounded by the world we must automatically know it well. Beginner artists who work straight from memory are often disappointed when they discover that their knowledge of nature is too vague to be practical.

Drawing not only challenges our belief in our innate ability to see, it also provides us with a new set of tools to develop a true understanding of the visual world.

In her diary Rachael writes:

Our business is to become better (in every sense of the word) human beings, and Art is only to be regarded as an inestimable aid in making us so. Its chastening and intensifying power cannot be over valued — but never lose sight of the fact that it is only a means.

With these words Rachael invites us to consider how drawing’s lessons in vision can inform a more general outlook on the world. Over the coming weeks, as we explore Rachael’s art and lessons on drawing, I invite you to think about art not as an act of creation but as an act of deep observation.

Very Respectfully yours,

Courtney Clinton

Be sure to check out the WCAX interview below with Courtney Clinton and Allison Gregory!

Rokeby Museum is excited to offer this 6-part series from artist in residence Courtney Clinton. Please consider a donation, if you can, to help us continue to offer programs like this.

Rokeby Museum

Rokeby Museum

How do I sign up for this distance drawing/art course?

Hi Julie,

The beauty of this course is that you don’t need to sign up! Just follow along as the lessons come out. To ask questions or get feedback, share your work on instagram and tag @clinton.courtney and @rokebymuseum and use the hashtags #RokebyDistanceDrawing and #DrawingWithRachael.

You can also email questions and images to Allison here at Rokeby. Have fun and we want to see your work!

I would like to sign up for this 12 week course. I live in Virginia USA

Botanical drawings and paintingss have been my favorite things since I can remember. “Deep observation” also appeals to me. I need to draw.

This is wonderful! Thank you, Julie and Rokeby Museum for thinking of this.

I teach watercolors , pastels and drawing to senior citizens, I teach 4 classes a week and am so excited to past on this information on to my students. I am always growing as an artist myself so I am so excited about this course . I believe you learn something new each day even in my senior years.

Thank you! We are so excited to be sharing this and we can’t wait to see everyone’s art!

Courtney

This looks so interesting. I am an art teacher heading back to classes next week. Can’t wait to follow along on this. Do we need to sign in to get the weekly updates?

Thanks,

Barb

Hi Barb, no need to sign in, just follow along here at the Rokeby blog and watch for our new posts! The schedule for new lessons is below. Enjoy!

July 27: Vision

August 10: Copying

August 24: Mistakes

September 7: From Life

September 21: Self Critique

October 5: Illustration

Hi Barb,

As an art teacher I can’t wait to hear your thoughts on the course. I did an interview for the James Gurney blog over the weekend and we discussed how much art education has changed since Rachael’s time. You don’t need to sign up but we encourage you to share your drawings (and your thoughts) on social media and tag us with the #RokebyDistanceDrawing and #DrawingWithRachael hashtags!

Courtney

Here’s the link to Courtney’s interview with James gurney: http://gurneyjourney.blogspot.com/2020/08/rokeby-remote-learning-course.html

Love a good challenge! I’m in!!

Hi Sara!

Fantastic! I can’t wait to see you art 😀

Thank you for this lesson. It is insightful and inspiring.

I am so happy to be able to see into the past with you, and work through the 12 weeks of drawing and history!

Karen

Hi Karen,

Thank you for your kind words! We have had so much fun putting this course together and we are excited to see everyone’s art! Please share your art and reach out with questions! 😀