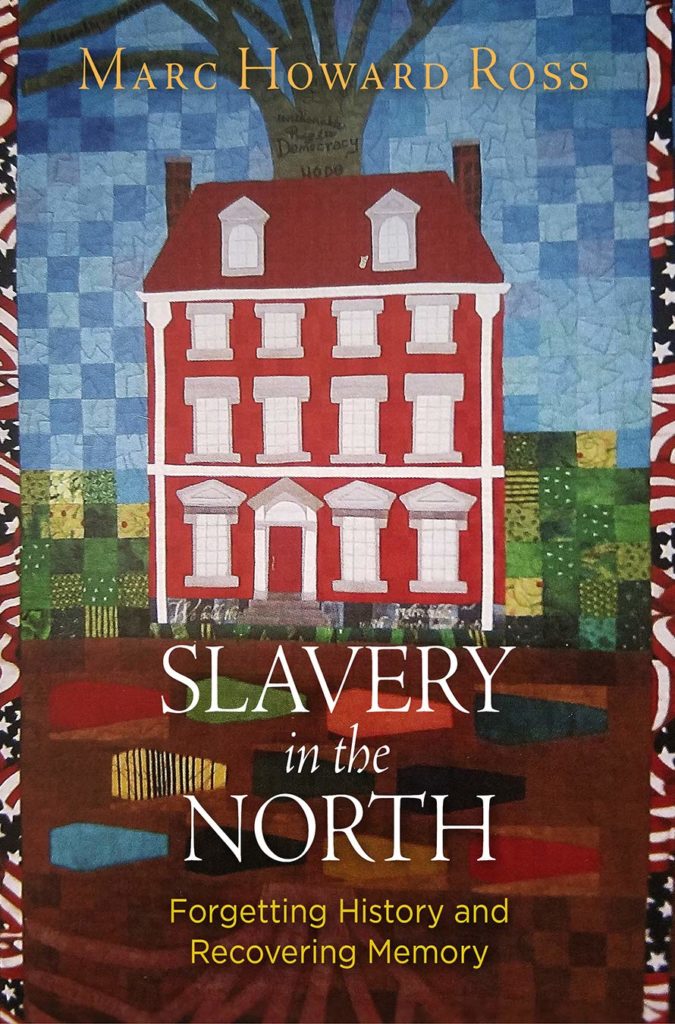

Book Review: “Slavery in the North” by Mark Howard Ross

by Joan Gorman, Rokeby Museum Visitor Services Coordinator

Northerners have a tendency to think that where slavery existed at all it was on a smaller scale and the enslaved were treated better than the enslaved in the South.

The dust jacket of Slavery in the North: Forgetting History and Recovering Memory, by Marc Howard Ross, might give one the impression that the book is less than the scholarly, meticulously researched, book that it is. It is a serious discussion of the collective forgetting of history and the collective rekindling of the memories of the actions of our ancestors. Slavery in the North is tightly structured; Ross lays out his theses, uses examples to illustrate them, and sums them up at the end of each chapter to keep his arguments on track and to cogently develop and present his conclusions.

Ross uses the reality of slavery in the North to illustrate the ways by which societies forget their past — whether on purpose or by neglect. A very long introductory chapter addresses the theories of collective forgetting and remembering, pointing out the differences between how slavery in the North and slavery in the South are viewed, especially by the enslavers’ descendants.

Northerners have a tendency to think that where slavery existed at all it was on a smaller scale and the enslaved were treated better than the enslaved in the South. While largely true that fewer were enslaved in the North, there were other ways that Northerners directly or indirectly participated in the perpetuation of slavery, facts that, as they come to light, both shock and surprise most Northerners. For example, many New Yorkers, myself among them, had no idea that there was a slave market at Wall and Winter Streets, that there were still enslaved people in New York in the early 1800s, or that the first enslaved Africans arrived in 1626 while the city was under Dutch rule.

Northerners have largely discounted the role that the Northern ports played in the slave trade. Northerners whose families arrived well after the Civil War and emancipation feel that their ancestors had no part in slavery but ignore the fact that their educational and economic opportunities were formed by the labor of enslaved people. An example of this is the endowments given by the Royall family to found Harvard Law School. Their money was earned in the slave trade and on Isaac Royall’s sugar plantation in Antigua.

Exploring the concept of collective remembering, Ross discusses how memories are recovered through media presentations, museum exhibits, and shift in beliefs and how they can be used going forward through narratives and rituals, enactments, and visible public displays. The heart of the book is devoted to specific examples of sites where memories were recovered, the controversies surrounding the memorials constructed, and the process by which compromise was eventually reached. For instance, the rediscovery that George Washington brought nine enslaved people to work in his house in Philadelphia prompted the creation of a memorial on the site; the rediscovery of an eighteenth-century African Burial Ground in Lower Manhattan led to the creation of a National Monument, a National Park Service site, and the home of the first slavery memorial built on federal land.

This is a thought-provoking and important book, instructive about the past and suggestive of ways to move forward. Ross’s writing is clear and concise, his ideas well-structured, organized, and eye-opening. I highly recommend this work.

Joan Gorman is the Visitor Services Coordinator at Rokeby Museum.

Rokeby Museum

Rokeby Museum