The Jagged Edges of Progress

by Elise A. Guyette, Ed.D., Rokeby Museum Trustee

Part I (1776–1870)

“Disillusionment inevitably follows each moment of heightened hopes and expectations by people of color.”

— Elizabeth R. Bethel, Historian

The truth of Bethel’s assertion can be seen through the generations of the Robinson family who first migrated from England to Rhode Island, where the slave trade was dominant in the 18th century, especially in Narragansett County where the Robinsons settled. They operated a large plantation worked by enslaved peoples. Those who migrated to Vermont were devout Quakers, who had come to eschew slavery, and they established their farm at Rokeby in Ferrisburgh, VT. They and their descendants lived there from the 1790s to the 1960s.

The inhabitants of the house lived through points of heightened hopes for African descended people such as the Revolution, emancipation, and a renewed interest in civil rights for all. They also lived through violent backlashes against people of color evidenced by scientific racism, the violence of Reconstruction, and the establishment of a prison-industrial complex.

This article, in three parts, explores those high and low points as well as the tentacles of that history that reach into the present.

High Hopes: Revolutionary Era

During the lives of Rokeby’s founders, Thomas (1761–1851) and Jemima Fish Robinson (1761–1846), the country experienced revolutionary change followed by a conservative backlash. The Revolution stimulated heightened hopes that freedom was finally coming for people of color. More people were freed during this era than at any other time before total emancipation in 1865. Black soldiers fought for both the British and American sides, since both nations vowed to abolish slavery if they won the war. For that reason, with hope in their hearts, Black men fought in the thousands to free the country from slavery.

In 1777, a Hessian soldier remarked, “No regiment is to be seen in which there are not negroes in abundance: and among them are able-bodied, strong, and brave fellows.”[i] However, the sacrifices that Black men and women made for the American side were not rewarded. The ensuing Constitution was a slaveholder’s document, defining enslaved people as 3/5th of a human being for purposes of Congressional representation. While the British freed the Black soldiers who had fought for them and their families, only individual American soldiers were freed as a reward for their military service. The institution of slavery remained in full force on American soil.

One glimmer of hope was the Constitutional clause that provided for the end of the overseas trafficking in human beings in 1808. Many felt that with the end of the horrors of the middle passage, slavery would wither. On January 1, 1808 many Black people met in their churches to praise the Lord that the end of slavery was near. However, their hopes were again dashed when the buying and selling of women, men and children increased internally in the country. The constant rapes of enslaved women in order to produce children born into slavery, a peculiarly American practice, eased the repugnant cravings of white supremacists for African people kidnapped from overseas.

Low Point: Post-Revolution and the Rise of Scientific Racism

After high hopes for equality during the revolutionary era were dashed, expectations for justice plunged. The founders of our country had maintained that all men were created equal, but after the country accepted the Constitution that preserved slavery, they needed to explain away the contradiction. Thus was born the assertion that Blacks and Whites had different blood that made Whites superior to Blacks. This “scientific racism” was not important before the war, but it became vital afterwards to get the founders off the hook of hypocrisy.

While Thomas and Jemima Robinson were settling into their new home in Ferrisburgh, an ominous character was singing and dancing across a stage in Philadelphia, the cradle of liberty. A dimwitted Sambo character created in 1795 for a play, “The Triumph of Love,” became a ubiquitous character in American culture ‘proving’ that Whites were the superior race.[ii] By 1820, the stereotype was firmly implanted in Whites minds. The 18th century character, along with other similar stereotypical images, lived on through the 19th to 21st centuries in minstrel shows and movies, at fraternity parties, as artifacts, and on food products.

Sambo was a difficult stereotype to fight, but Blacks heroically fought against it at every turn, asserting they could not talk it down but would live it down. Black communities, including one in Hinesburgh, built successful farms and businesses, sure that if they showed the world their skills, equality would surely follow. That movement showed promise as the abolition movement again gathered steam.

High Hopes: Abolition, Civil War and Emancipation

The next moment of heightened hopes dawned as the aim of ending slavery gradually became a goal for many Americans. The second generation of Robinsons, Rowland T. (1796–1879) and Rachel Gilpin (1799–1862) were not just anti-slavery advocates but radical abolitionists who believed in the equality of men and women, Blacks and Whites. They rejected scientific racism. They aided people who freed themselves from slavery, employed freed men and women on their farm, and hosted Frederick Douglass and other luminaries of the abolitionist movement at Rokeby. The Robinsons were instrumental in founding Vermont’s anti-slavery society, which was not popular at first, since many White people still believed that subordination to Whites was a natural condition for people of color.

In the North, a new idea gradually took hold among many Whites: the idea that Blacks were inferior but should not be enslaved. Some people supported Colonization, a scheme to uproot freed families and send them to Liberia. Others supported the idea that slavery should be contained in the South and not allowed to spread to the west. Kept in the South, people believed slavery would die a natural death. It was the need of southerners to spread slavery to other parts of the country, coupled with the abolition movement, that caused the southern states to write secessionist documents. Every one of these documents pointed to the slavery issue as the spark to secede from the Union. “Local control” was called upon only as a means to protect the system of slavery and to protect the wealth it produced for elite Whites.

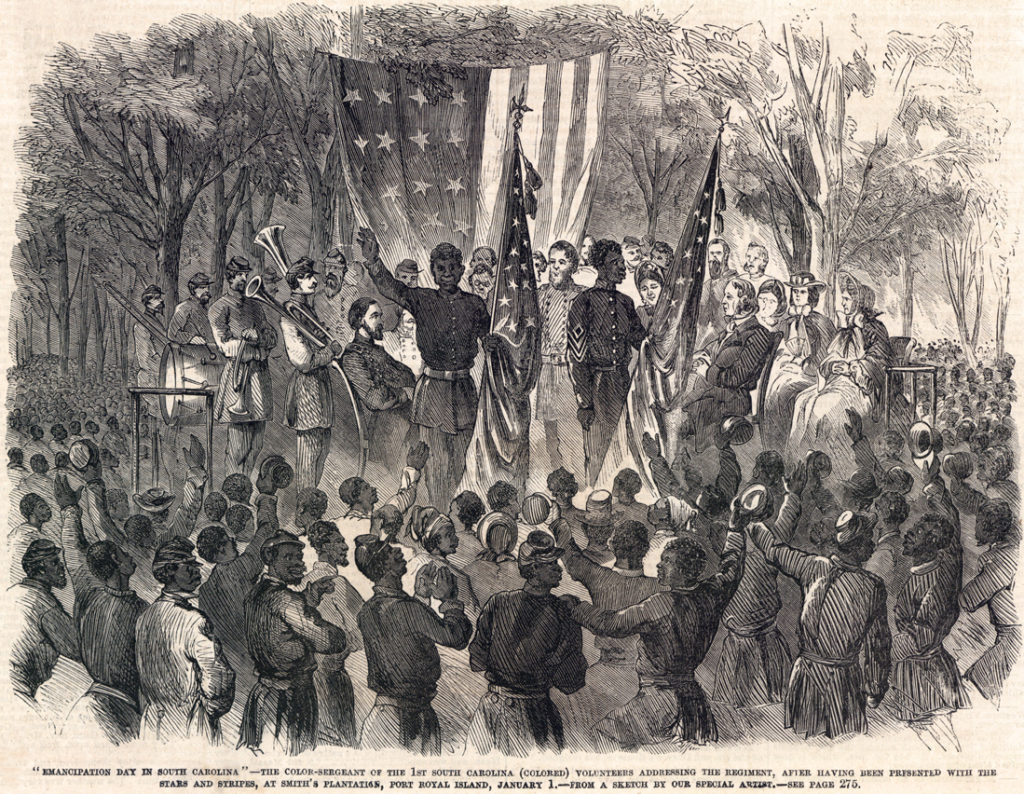

Blacks were joyful when the Union took to the battlefield against the Confederacy, and claimed the war as their Second Revolution. They felt sure the end was coming for slavery and itched to join the fight to prove their mettle but were not allowed, legally, until the 1863 Emancipation Proclamation.[iii] As in 1808, on January 1, 1863 many Black people met in their churches to praise the Lord that the end of slavery was near. One of these men hoping to fight against the traitors to our country was Aaron Freeman from Charlotte, who sometimes worked at Rokeby as a farm hand.

Finally, with emancipation, President Lincoln provided for men of color to join the military. Unfortunately, Rachel Robinson had died before she could witness emancipation, but Rowland T. lived through both the highs and lows of this era. Aaron Freeman and his cousins-in-law from Hinesburgh joined the MA 54th. This was another moment of heightened hopes for freedom and equality, as Black men helped to turn the tide of the war. By the end of the war, 10% of the Union army & navy were Black men, although they received less pay than Whites and could not rise above the rank of sergeant major. Yet, they rejoiced when freedom for all was finally attained through the 13th Amendment to our Constitution. Black men and women emerged from the war years with very high hopes. Freedom had come. But what would it look like?

Part I Endnotes

[i] W. B. Hartgrove (1916). “The Negro Soldier in the American Revolution” in The Journal of Negro History Vol. 1, No. 2 (Apr., 1916), pp. 110–131. Online

[ii] John Murdock (1795). The triumphs of love; or, Happy reconciliation. A comedy. In four acts. / Written by an American, and a citizen of Philadelphia; Acted at the New Theatre, Philadelphia. (Philadelphia: Printed by R. Folwell, September 10, 1795). Online

[iii] There were three Black regiments established in 1862 that were already in the field and fighting: 1st LA Native Guard, 1st KS Colored Volunteer Infantry, and the SC 1st.

Part II (1868–1890)

“Black progress is always met with a violent backlash.”

— Ta-Nehisi Coates, Author and Journalist

In Part I, we recalled the heightened hopes of progress for Black equality and backlashes against it in the 18th and first half of the 19th centuries. This installment continues with those patterns in the later half of 19th century.

Low Point: Presidential Reconstruction

Rowland E. (1833–1900) and Ann Stevens Robinson (1841–1920) were active artists and writers during the Reconstruction era. They were not advocates for social justice and equality like their forebears but were active in literature and artist circles. As a young man Rowland E. wrote disparagingly of people of color and immigrants, who began to flow into the country after the war and, later in life, characters in his Danvis tales exhibited racism, sexism and xenophobia. They made no public statements about advancing rights for newly freed men and women. As in many families, the children voiced different views from their parents. Just how different Rowland’s views were from his parent’s is a topic currently under study.

After Lincoln’s assassination, Andrew Johnson became president. As soon as the 13th, 14th, and 15th amendments were ratified Johnson declared that Reconstruction was over. A white supremacist from Tennessee, Johnson had approved when the Confederate states wrote new constitutions that kept Blacks in neo-slavery. Their high hopes for equality were once again dashed as Johnson restored ex-Confederate’s citizenship by executive order while Congress was in recess. Johnson restored their former lands to them (lands that were then owned and worked by freed people), welcomed them back to Washington, D.C. and ensured that freed people were by no means really free to exercise their rights.

High Expectations: Congressional Reconstruction

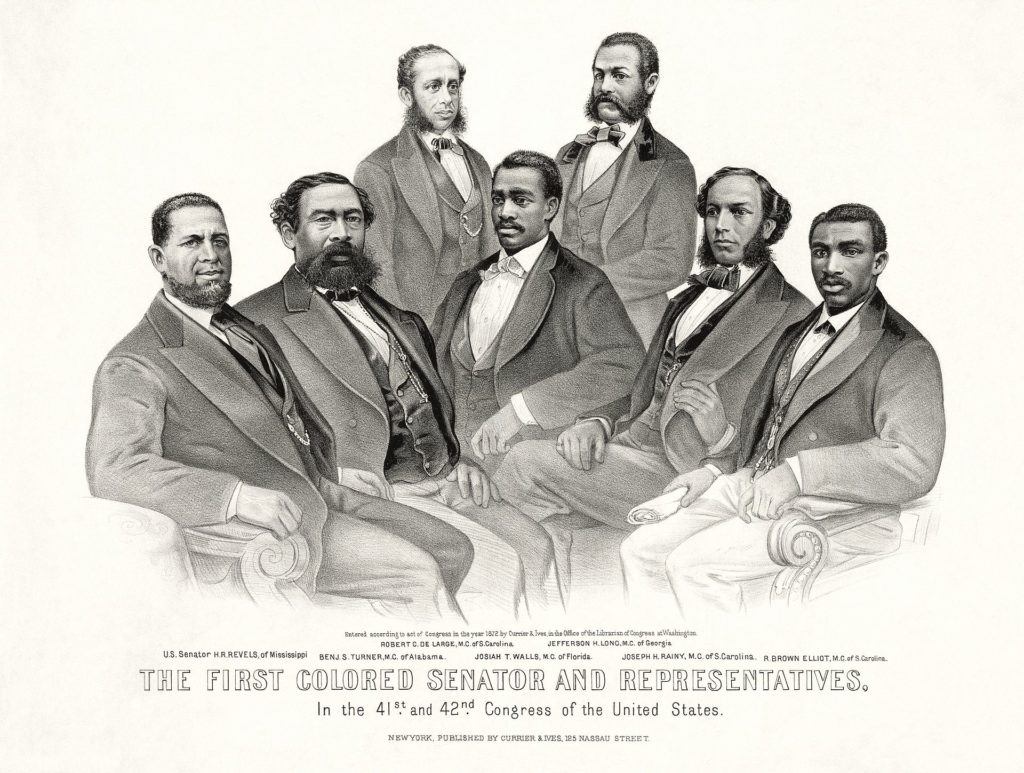

However, after Congress returned to Washington, Republicans began an era of Congressional Reconstruction. Congress mandated that the southern states rewrite their post-war constitutions to include civil and human rights for all. Loudon Langley from Hinesburgh, who had moved to Beaufort, SC with his family after the war, was a delegate to the 1868 SC Constitutional Convention. This biracial convention wrote the most progressive document of the era.[i] The state began breaking up the old plantation system and providing land to those who had labored on it for nothing while building up the wealth of privileged Whites.

The new biracial Reconstruction governments instituted taxes in order to rebuild the South and actually pay everyone for his/her work. The tasks were enormous, especially in the face of colossal resistance from ex-Confederates. Because taxes would benefit freedmen, they fought against them at every turn, as so often happens today for similar reasons. However, throughout the South, the biracial governments made amazing headway, providing for healthcare, housing, and education for all people. They rebuilt infrastructure destroyed by war and alleviated hunger. They created legal codes, dealt with issues of discrimination and justice and created biracial courts. They cleaned up the electoral processes, and the freed people were citizens for the first time in their lives. They finally had a country and a flag of which they were proud.

They did all of this while trying to stay alive as terrorists groups such as the KKK, the Knights of the White Camellia, and Red Shirts fought their every move. But people of color had the power to thwart them, and the federal government had the will to protect newly won rights. There were Black US Congressmen, school board commissioners, sheriffs, merchants, auditors, lawyers, teachers, and the like. Loudon Langley, originally from Hinesburg, was the first superintendent of schools in Beaufort County and was appointed auditor for the town of Beaufort, SC. Blacks were taking full advantage of the 13th, 14th, 15th amendments.

Finally, Congress enacted the Civil Rights Act of 1870, also known as the Enforcement Act or the First Ku Klux Klan Act. It mandated enforcing the terms of the 14th and 15th Amendments. Terrorists were arrested and imprisoned. The federal government stood steadfast in its support of Black rights, and terror organizations were dwindling. The 1862 Morrill Act funded land grant colleges throughout the country, and Black men and women attended them in the South.

Progress had begun. Optimism grew. There was great hope that Blacks would finally be treated as free and equal. What happened to that promise of a better life?

Low Point: Reconstruction Ends and New Oppressions Appear

W. E. B. De Bois wrote, “If there was one thing that (ex-Confederates) feared more than bad Negro government, it was good Negro government.”[ii] It undermined the idea of white supremacy, so they needed to end it one way or another.

White supremacists assassinated Black office holders. They lynched Black men who voted and sometimes their wives and children to instill the greatest amount of terror. They murdered, raped, and tortured many people who were fighting for equal rights. Stories like this one from Frances Thompson in Memphis were ubiquitous:

Tuesday night, seven men, came to my house. One of them hit me on the side of my face and, holding my throat, choked me. Lucy (16) tried to get out of the window when one of them knocked her down. They drew their pistols and said they would shoot us and fire the house if we did not let them have their way with us. All seven of them violated us.[iii]

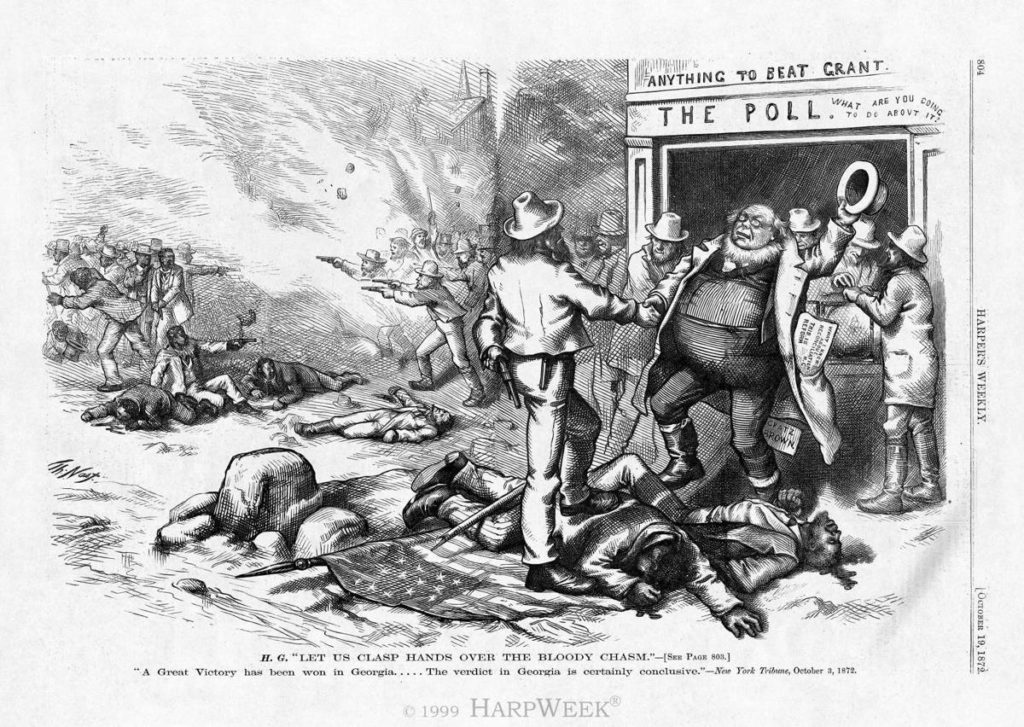

By the 1876 presidential election, the federal government was wearying of this second fight against the Confederacy, although they still had troops in Louisiana and South Carolina to protect the biracial legislatures that still existed there. Industrialists in the North were tired of the animosity between North and South since they needed the South’s cotton for their mills. Vermont was no exception, as mills in the state vied for cotton. North and South finally shook hands over the bloody divide, and the end was near once again for hopes of Black equality.

Before the final election of Reconstruction, an ex-Confederate general in SC, Harrison Butler, claimed that there had to be a certain number of leading Black men killed. If they found out after the leading men were killed that they couldn’t carry the state, they were going to kill enough so that they could carry the majority.[iv] The 1876 election was a brutal one, but by voting in the face of grave dangers, loyal Blacks ensured a victory for Republican Rutherford B. Hayes as US President. Their reward: Hayes withdrew all remaining federal troops from the South and left the states to “local control.” The Civil Rights Act of 1875, which forbid discrimination in public spaces, was to be enforced by ex-confederate traitors who had no interest in protecting the rights of people of color. In 1883, the US Supreme Court even declared the act unconstitutional.[v] After eight years of biracial governments that went a long way to rebuild the South and ensure equality, rights for people of color were doomed yet again.

With no interference from the US government, Southern states proceeded to build a barbarous system of neo-slavery. Not only did people of color lose their jobs and political positions, but Blacks were also barred from an education at institutions that previously had accepted them. They were forced to sign work contracts for White planters on terms enormously advantageous to the Whites. If Black men and women refused to sign contracts, they were arrested. Sharecroppers were cheated left and right. If they complained, they were tortured, raped, and lynched. Blacks were also arrested for walking near RR tracks, for not getting off the sidewalks quickly enough for Whites, for resisting rape. If they complained, they were tortured, raped, and lynched. Those arrested were then legally re-enslaved, because of 5 words in the 13thAmendment, which abolished slavery “except as punishment for crime.” Industrialists leased prisoners to slave in their companies and on their farms. Neo-slavery and the prison-industrial complex were in full swing in the South.[vi] Once again Black people were put to work building wealth for elite Whites.

New stereotypes were cemented in White brains. So many Black people were imprisoned that White people came to believe they were naturally criminal. Any resistance, and Blacks were defined as “rioters” who needed to be stopped. Peaceful demonstrations by people of color resulted in torture, rape, and lynching by white supremacists. Any movement toward wealth and equality enraged many Whites, and was met with angry mobs murdering thousands across the South and destroying successful Black towns (e.g. Colfax, LA; Tulsa, OK; Rosewood, FL). This ensured that Blacks could not pass on wealth to future generations. Few White people died in these actions, but 10,000 to 20,000 men, women and children of color died at the hands of enraged Whites. The bones of these people are still being found today in southern states.

Ida B. Wells summed up the era this way:

It was a long, gory campaign; the blood chills and the heart almost loses faith in Christianity when one thinks of … the countless massacres of defenseless Negroes, whose only crime was the attempt to exercise their right to vote. Scourged from his home; hunted through the swamps; hung by midnight raiders, and openly murdered in the light of day, the Negro clung to his right of franchise with a heroism, which would have wrung admiration from the heart of savages. He believed that in the small white ballot there was a subtle something that stood for manhood (and) citizenship, and thousands of brave black men went to their graves, exemplifying the one by dying for the other.[vii]

Reconstruction was not a failure of Black leadership. It was a failure of all branches of our federal government to enforce the 14th and 15th Amendments to our Constitution. According to historian Randolph Roth, the United States emerged from Reconstruction with a much higher homicide rate than other western nations. Racial violence was the overwhelming factor in this dramatic increase in the rate of death, and the high rate of American violence has persisted to the present day.[viii]

The mindset of Blacks as criminals is still with us as students of color are disproportionately suspended from school, Black drivers are stopped in disproportionately high numbers by police, and Black men and women are disproportionately represented in our prisons. Many are guilty of nothing other than being Black with few resources to fight the system.

A Bright Spot: Education

In 1878, one year after the end of Reconstruction and one year before he died, Rowland T. Robinson wrote to his friend William Lloyd Garrison in Boston to ask for advice on how best to apply a philanthropic bequest of a friend, “with reference to our colored population, especially the freedmen at the South.” Garrison replied, “Unquestionably, next to the protection of their citizenship, what they most stand in need of is education, in all its branches; and this is naturally to be sought through those institutions which have been organized expressly for that object.”[ix]

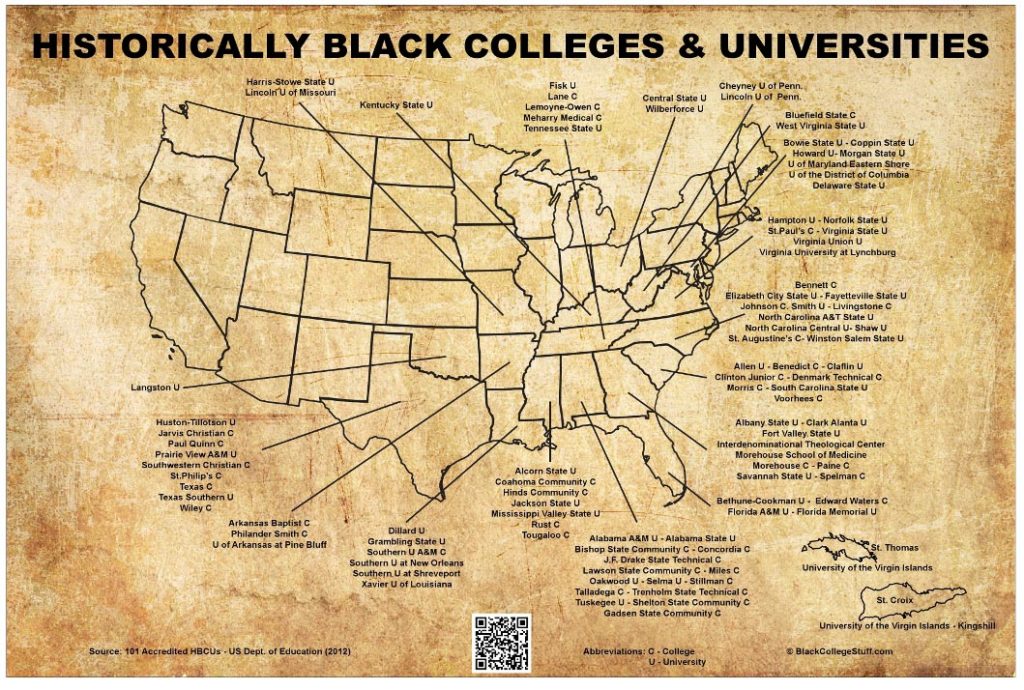

In 1890, Senator Justin Morrill from Vermont, who had authored the first Morrill Act in 1862 authorizing land-grant colleges to teach agricultural and mechanic arts, pushed through a second Morrill Act. It stated that any land-grant institution that discriminated against Blacks would not receive federal monies. As a result, southern states built separate colleges for Blacks, which (added to Black colleges already established) became the system of Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs) still functioning today.[x] The 1890 schools were all co-ed from the beginning, expanding democracy among people of color.[xi]

Part II Endnotes

[i] Eric Foner, Reconstruction: America’s Unfinished Revolution, 1863–1877 (NY: HarperCollins, 1988), p. 329.

[ii] W.E.B. DuBois. Black Reconstruction in America (NY: Harcourt, Brace and Co., 1935; reprinted 2013) p. 381.

[iii] Dorothy Sterling, Ed. The Trouble They Seen: The Story of Reconstruction in the Words of African Americans (Boston: Da Capo Press, 1994), p. 93.

[iv] Testimony as to the denial of elective franchise in South Carolina at the elections of 1876, Senate Miscellaneous Document, 44th Congress, 2nd Session, No. 48, p. 45. This was no idle threat. In July of 1876 the infamous Hamburg Massacre of Black men occurred.

[v] This is similar to the declaration of the US Supreme Court in 2013 that invalidated the 1965 Voting Rights. This left southern states to take over local control of voting mechanisms. The result has been machinations, such as closing polling stations in majority Black districts, calling for picture IDs, and other ploys to keep Blacks from voting. In essence, it has caused the disenfranchisement of many Blacks.

[vi] See Douglas Blackmon. Slavery by Another Name: The Re-Enslavement of Black Americans from the Civil War to WWII. New York: Anchor Books, 2009.

[vii] Ida B. Wells-Barnet (1895). A Red Record: Tabulated Statistics and Alledged Causes of Lynching in the United States. In Chapter One: “The Case Stated”. Online

[viii] See Randolph Roth. American Homicide. Cambridge: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2009.

[ix] Letter to Rowland T. Robinson from Wm. Lloyd Garrison, Boston, July 11, 1878.

[x] Those already established were Berea College (est. 1855), Fiske University (est. 1866) and Hampton University (est. 1868). These were private co-ed universities.

[xi] Ironically, the last group welcomed into the land-grant system was Tribal Colleges for Native Americans. It was their stolen lands that were transferred to the states to fund the colleges in the first place. They had paid with their lives and their lands but reaped no benefits until 1994.

Part III (1890–present)

“Ignorance allied with power is the most ferocious enemy justice can have.”

— James Baldwin, American Novelist and Activist

In Parts I and II we recalled the heightened hopes of progress for Black equality and backlashes against it in the 18ththrough the 19th centuries. This installment continues with those patterns into the 20th and 21st centuries, beginning with the lowest point, the nadir of race relations in our country.

Low(est) Point: Turn of the Century

Many Black leaders of the continuing struggle for civil and human rights received their educations at HBCUs and used their knowledge and skills to challenge white-supremacist legislation. Rowland T. (1882–1951) and Elizabeth Donoway Robinson (1882–1961) lived through the era often referred to as the “nadir of race relations” in this country. They did not publicly state what they thought of the growing violence and segregation in Jim Crow America.

In the late 1880s, southern states began mandating segregation in railway carriages, which had been illegal during Reconstruction. Blacks viewed mounting segregation with horror, and some launched campaigns against it, sure the Constitution would protect them. In 1892, activist Homer A. Plessy agreed to challenge the new segregation rules. He bought a ticket on a train leaving New Orleans and chose a seat in a whites-only car. The conductor insisted he move, which he refused to do. He was arrested, jailed, and convicted of violating Louisiana law.

Plessy challenged the law as violating the Equal Protection Clause of the 14th Amendment. In May 1896, the US Supreme Court ruled that separate-but-equal was constitutional. The ruling ensured the survival of the discriminatory legislation for the next half-century. It led to segregation on buses, in hotels, theaters, swimming pools and schools. By 1899, separate-but-equal was enshrined as constitutional throughout the country. The barbarity of Jim Crow legislation to enforce segregation had free reign.

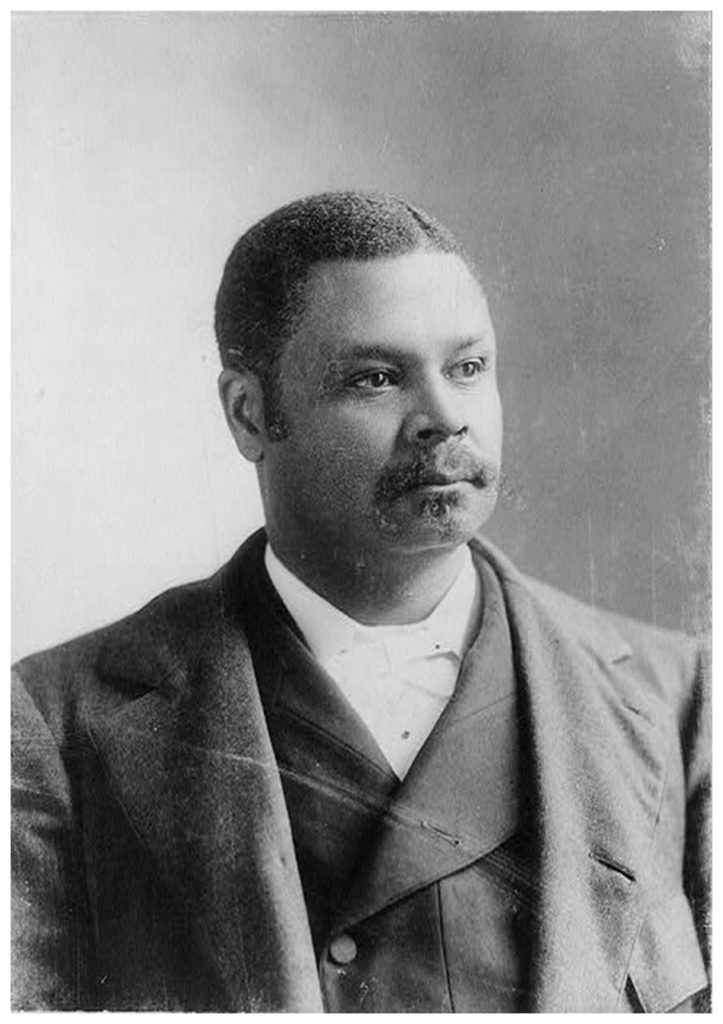

In 1901, the last Black Congressman left in our nation’s capitol gave a farewell speech to Congress. George H. White of NC emphasized the victories of Reconstruction:

Since the end of slavery, African Americans had accumulated almost a billion dollars in personal and real property, raised millions for education, created 20,000 churches and thousands of schools, and the production of cotton in the South had more than doubled. … These parting words are on behalf of an outraged, heart-broken, bruised, and bleeding, but God-fearing people, faithful, industrious, loyal people—rising people, full of potential force. … The only apology that I have to make for the earnestness with which I have spoken is that I am pleading for the life, the liberty, the future happiness, and manhood suffrage for one-eighth of the entire population of the United States.[i]

Black women were fully engaged in the heroic struggles for justice and equality. In 1896, Mary Church Terrell became the first President of the National Association of Colored Women. She maintained that Black women had a vital role in improving conditions for their people. After all, they had already established kindergartens and training schools for nurses, aided the indigent, orphans, and the elderly, looked after truant children, rescued unfortunate women, and sewed clothes for the needy. Women petitioned their state legislatures “to repeal the obnoxious Jim Crow car laws.” They fought against the “barbarity of the convict lease system, of which Negroes especially the female prisoners are the principal victims, with the hope that the conscience of the country may be touched and the stain on its escutcheon be forever wiped away. …Lifting as we climb, onward and upward we go, struggling and striving and hoping that the buds and blossoms of our desires will burst into glorious fruition ere long.”[ii]

Terrell was also a charter member of the NAACP, organized in 1910. Its stated purposes were to “emancipate in fact … a race of nearly 12,000,000 American-born citizens.” Among other issues, the organization worked to abolish legal injustices, stamp out race discriminations, and “prevent lynchings, burnings and torturings of Black people.”[iii]

In response, President Woodrow Wilson totally segregated the federal government. Blacks and Whites had worked together for decades in the Post Office and the Interior Department. He ended that, and many people lost their jobs. In 1915, Wilson screened the movie the “Birth of a Nation” in the White House. The movie contained every vile stereotype of Black Americans that had ever been conceived and portrayed the Ku Klux Klan as the heroes of our nation. Wilson proclaimed it a wonderful, historically accurate account. The Klan, which had been almost wiped out by the 1870 Enforcement Act, began to flourish once again. Monuments to the traitorous Confederacy were erected. Lynchings, rapes, and torture increased. Crowds of White people packed picnics and enjoyed a wonderful time, while others tortured, burned, and hung people of color for their entertainment. They created postcards of the brutal, painful scenes and sent them to their friends and relatives in other states.

Huge out-migrations ensued beginning about 1915 through mid-century, as thousands upon thousands of Southern Black people fled to the north, midwest, and west to try to find a space in which they could simply live in peace and flourish as American citizens. They became refugees in their own country. However, northern cities forced them to live packed tightly in certain areas. They drew red lines around the areas, and banks refused loans to anyone living there. They were hired for only menial service jobs with low pay. Black veterans could not use the GI Bill. The police surveilled the areas constantly, arresting Blacks in much higher percentages than Whites. They had not discovered justice and equality in the North. They continued their struggles.

Heightened Hopes: Yet Another Civil Rights Movement

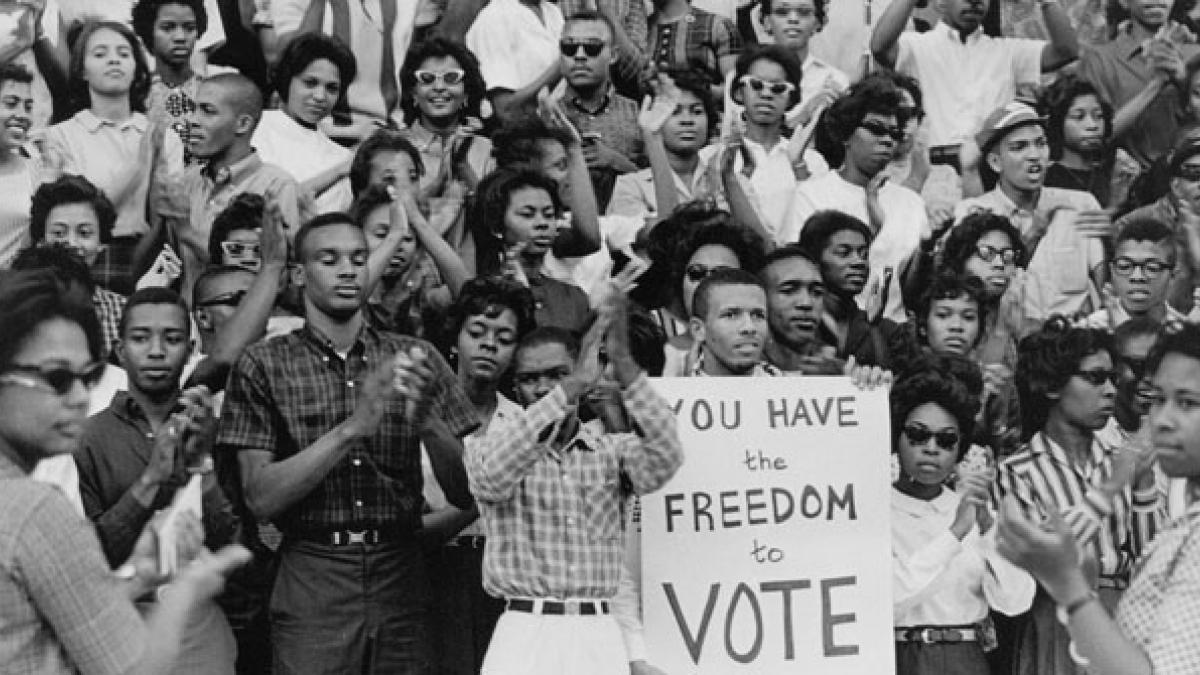

People of African descent in this country have never stopped fighting for their rights, and they certainly continued their struggles throughout the Nadir period. Finally, their struggles began to show promise (yet again). In 1954, the USSupreme Court issued its decision in Brown v. Board of Education. School segregation was declared illegal. Hopes soared that segregation in other areas would end. Freedom riders tried to desegregate public transportation (yet again), young people sat at lunch counters and were spit on and burned with cigarettes, people were murdered for registering to vote or for registering others (yet again). Adults and children endured all kinds of pain and humiliation at the hands of police and the public. Children were humiliated and terrorized for simply going to school. Four girls died in a 1963 bombing in Birmingham, AL where months earlier the police had attacked a peaceful march of school children with water hoses, batons and police dogs. This was yet another long and brutal battle against white supremacy with no end in sight.

However, in 1964 Congress finally passed yet another Civil Rights Act, which prohibited discrimination based on race, color, religion, sex, or national origin. It banned racial segregation in schools, employment, and public accommodations. In 1968 yet another Civil Rights Act, known as the Fair Housing Act, prohibited discrimination in the sale or rental of housing nationwide. Until that time, there were codicils attached to many deeds forbidding the sale of housing to non-whites, e.g. Mayfair Park in South Burlington.

Even after this newest Civil Rights Act, Blacks still faced many obstacles to attaining the vote. Finally, the vicious beatings of civil rights activists on the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, AL led to passage of the 1965 Voting Rights Act. The Act prohibited the many voter registration requirements used to keep Blacks from exercising their rights. The federal government once again enforced the 15th Amendment to the US Constitution. It had been 100 years since the end of the Civil War and final emancipation, and people of color were again able to exercise the rights they had exercised during Reconstruction.

This eventually led to the election of Barack Obama as the first Black president of our country. People who did not understand the jagged edges of progress for Blacks in the US, breathed a sigh of relief. The country was in a new “post-racial” era where all were treated equally and justice reigned in the land.

Low Point: 2013 to present

In 2008, the election of Barack Obama was only an apparent victory for the forces of equality. As always, heightened hopes were followed by a backlash. In 2013, the US Supreme Court gutted key parts of the Voting Rights Act of 1965. In 2016, a man was elected to the highest office in our country, who opined the next year that there were “very fine people” on both sides of the deadly white supremacist rally in Charlottesville, VA. In July of 2020, the Administration repealed an Obama-era rule that reinforced the 1968 Fair Housing Act “requiring cities to more rigorously examine local housing patterns for racial segregation and come up with plans to address any measurable bias.”[iv] Fair housing advocates have condemned the action.

People who believed we were post-racial had let down their guard because, as James Baldwin said in a letter to his nephew, “White people are trapped in a history they don’t understand and until they understand it, they cannot be released from it.”[v] Averting our gaze to other issues allowed the dark powers of racism to creep freely through the country once again.

The lesson for all of us is that we have never been post-racial. As soon as we think we’ve won some victory for humanity and turned our gaze to other issues, a racist backlash occurs. The violent stage in which our country is once again embroiled was predictable. Perhaps this newest protest movement against violence and institutional racism, precipitated by the newest murders of men, women, and children, will meld into another moment of heightened hopes. History tells us it might be so. But we need to be vigilant if we want to make lasting change. We can never let down our guard or, like a virus, racism will emerge from the darkened places in which it lurks and wreak havoc once again on people’s hopes and aspirations for justice and equality.

Part III Endnotes

[i] George H. White, “Defense of the Negro Race–Charges Answered. Speech of Hon. George H. White, of North Carolina, in the House of Representatives, January 29, 1901.” (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1901), pp. 13–14. Electronic edition. After White, no African American was elected to Congress from the South until 1972; none from NC until 1992.

[ii] Mary Church Terrell, “What Role Is the Educated Negro Woman to Play in the Uplifting of Her Race?” In D.W. Culp, Ed. Twentieth Century Negro Literature (Toronto: J. L. Nichols & Co, 1902), pp. 174-176. Online at the Gutenberg Project.

[iii] Principles of the NAACP (1911). In Deirdre Mullane, Ed. Crossing the Danger Water: Three Hundred Years of African-American Writing (NY: Anchor Books, 1993), p. 435.

[iv] Brenda Richardson. ‘We Could be Living in the 1890s’: How Housing Discrimination is Still Perpetuated Today in Money, August 24, 2020.

[v] James Baldwin. “A Letter to My Nephew”, December 1, 1962

Elise A. Guyette, Ed.D., is a former public school teacher, museum educator, and college professor, who has worked as a consultant on ethno-history, social sciences, and curriculum development for schools, theaters, television, and museums. She has a passion for discovering and teaching about stories that were lost because of the traditional telling of history from the point of view of the powerful and is currently working with Historic New England to tell the stories of past and present migrants to Burlington’s Old North End. Her publications are varied and include:

- Vermont: A Cultural Patchwork

- “Writing Oneself into Being: Black Writers and the U.S. Census”

- “Gandhi in South Africa: A Perfect Miracle or Political Expediency?” and

- Discovering Black Vermont, for which she was awarded the 2010 Richard O. Hathaway prize for the year’s outstanding contribution to the field of Vermont history. (Recently reprinted by VHS.)

Rokeby Museum

Rokeby Museum