Taking & Making Photographs in 1900

The following commentary by Ric Kasini Kadour, Curator of Contemporary Art at Rokeby Museum, is from the exhibition catalog that accompanies “Rokeby Through the Lens” on view at Rokeby Museum, May 19-June 16, 2019.

Much has been written lately about the under-representation of women in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics fields, commonly called STEM. But if we need a role model from history, Mary Robinson Perkins (1884–1931) provides a great example of an original STEM girl. Known as Molly to her friends and family, she attended local schools, then Goddard Seminary in Barre, Vermont, and the University of Vermont. She studied both botany and art at the University and worked as a botanical artist for several years before her marriage to Llewellyn Perkins, a math professor at Middlebury College.

Molly had a keen eye for nature. In a journal entry on March 25th, 1900, the fifteen-year-old records her observations of animals around the house: blue jays and foxes. “I saw a partridge fly up from from bushes on the south side of the smoke house over the ‘old house.’” On May 9th, 1900, she speculates about how the weather will impact pests. “Maybe the late spring is so as to kill off new forest tree worms,” she writes. “A week ago Sunday, the 29th, we saw three nests of limb-caterpillars on the mountain.” And she documents various plants she finds. “I found two English violets this morning almost open.”

Molly’s photography demonstrates her aptitude for chemistry and mathematics. Starting in the 1880s, cameras became more available to casual users. In 1888, George Eastman introduced the Kodak No. 1 box camera. For $25 ($645 today), one received a camera loaded for 100 pictures. Once the pictures were taken, the user returned the camera to Kodak for processing. Their slogan, “You press the button, we do the rest,” revolutionized the photography business and popularized photography. This made photography an easy, convenient hobby, but this is not how Molly embraced photography.

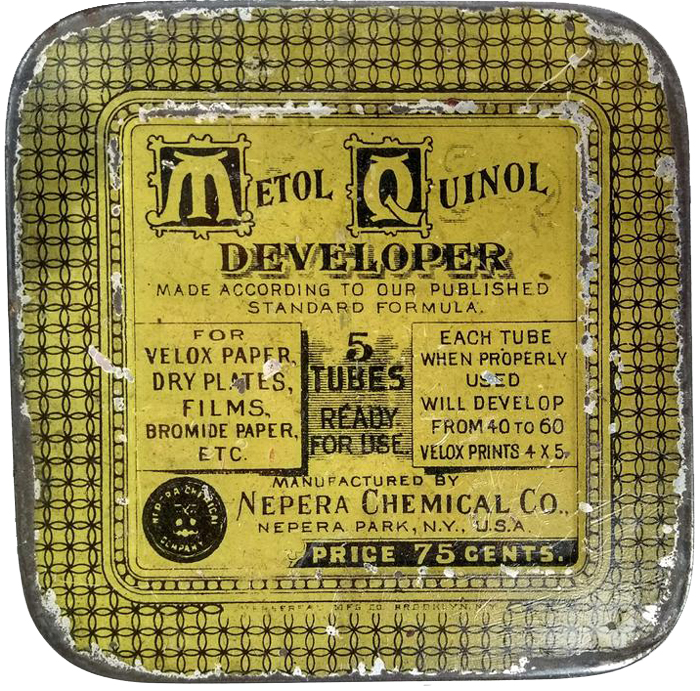

Molly not only owned a camera, but developed her own film as early as 1899. A number of photographs on white card frames are attributed to Molly on the back. Molly’s journal from 1900 mentions various outings and trips where she “took several pictures.” At one point, having missed a picnic, she waited for the goers’ return. “I got in the bushes and when the team with the young people came along I took their picture with my camera.” Her accounting journal from July 1901, records purchasing “Metol Quinol Developer, 15¢, Plates 50¢, Fixing and toning solution, 50¢.” Her journal records the output of her darkroom work. “Thursday night I developed two negatives, and Friday morning I developed four more: one of a kitten, one of Katharine Collins, one of Coral and one of the woods at the mountain; one of a load of wood with George and Rachael on top; and one of Faith & Hattie Chapman. I printed some Friday night.”

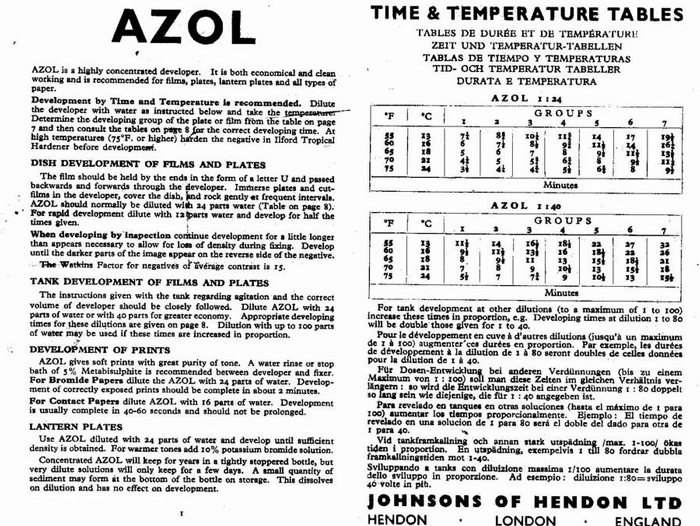

Molly was shooting pictures on plates and developing them herself. These were small acts of science that involved measuring powders and water and soaking plates or prints for different times depending on the temperature. One instruction from the period reads, “For tank development at other dilutions (to a maximum of 1 to 100) increase these times in proportion, e.g. Developing times at dilution 1 to 80 will be double those given for 1 to 40.” Molly’s casual mastery of the process shows a genuine aptitude in the fifteen-year-old.

Molly also demonstrated an interest in engaging with the world of photography, a fast evolving medium at the turn of the century. “I have sent off for five catalogs of camera supplies,” she writes. “I would like to take Paine’s Photographic Magazine. It costs 60¢ a year, I think.” Paine’s was a new magazine in 1889 dedicated to “brother Camera Cranks” and edited with the amateur in mind. “It will concern itself solely with Amateur Photography and matters of cognate interest. Prizes will be awarded every month for Amateur competition, and every number will be freely illustrated with halftone reproductions of Amateur work.”* The magazine shared tips for up-and-coming photographers, articles about new developing techniques, stories from photographers. That the magazine was written for boys seemed of no concern to Molly.

Her family supported her endeavor. She writes on March 15th, 1900. “George took me to Vergennes so that I might get some Metol-Quinol Developer so that I could finish some photographs on Velox for a present for Faith. That evening I printed a picture of father and mother; one of Mill Chapman (on blue paper); one of Faith and Hattie C. and George and Kenneth Goss; and one of me.” Faith, a friend of Molly’s, was having a birthday party a few days later. The photograph of George Willard and Kenneth Goss shows two boys playing on a path at Rokeby. Molly mounted the photograph in a white card frame.

A selection of Molly Robinson’s photographs are on view in the exhibition, Rokeby Through the Lens, Sunday, May 19–Sunday, June 16, 2019. DETAILS

*Source: Paine’s Photographic Magazine. (1899-1901). Retrieved from https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/100593831

Rokeby Museum

Rokeby Museum