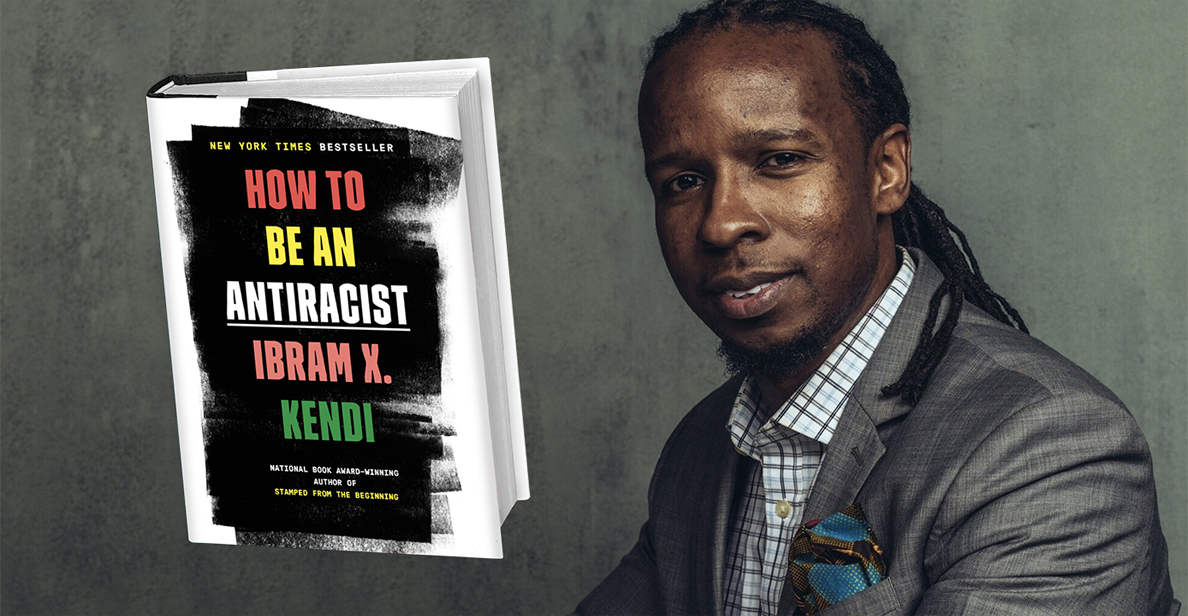

A Social Justice Primer — “How to Be an Antiracist,” by Ibram X. Kendi

by Richard Bernstein, M.D., Rokeby Museum Trustee

“…as Kendi’s awareness grew and as his thinking developed, he realized that the statement, ‘I am not a racist,’ which is meant to absolve the speaker of racist feelings or thoughts, actually expresses a level of denial that he calls ‘the heartbeat of racism.’”

Ibram X. Kendi’s book, How to Be an Anti-Racist, details his journey and his growing awareness of how racism informs his own life and thoughts. Along the way, he has taught himself how to be an anti-racist, and through his book, he speaks of and to himself as much as to the reader.

Born Ibram Henry Rogers, Kendi grew up in a middle-class household. His early years were spent in majority White schools where as a young boy he fought against the reality of racism in the classroom. He was not a good student, but he showed an aptitude for writing and won a Martin Luther King Day speech contest that propelled him on to college at the historically Black Florida A&M University. He earned a graduate degree in Black Studies at Temple University, taught race relations at American University, and is now the director of the Center for Antiracist Research at Boston University.

In his research on racism, much of it referenced in the book, Kendi discovered the story of Henry the Navigator, a 16th-century Portuguese prince, whose only connection to the sea was his initiation of the West African slave trade. He also invented the racial distinction that would assign blackness to a permanent underclass. Not wanting to bring the name of Prince Henry into the modern era, Kendi changed his middle name to Xolani, a Zulu name meaning peace.

This simple act of opposition to racism and racists is not what Kendi’s book is about, however. Popular discourse would have us believe that non-racism is the opposite of racism. But as Kendi’s awareness grew and as his thinking developed, he realized that the statement, “I am not a racist,” which is meant to absolve the speaker of racist feelings or thoughts, actually expresses a level of denial that he calls “the heartbeat of racism.”

According to Kendi, anti-racism is the true opposite of racism, which is rooted not in hatred, but in actual policies based on a racial hierarchy. A non-racist denounces racial hatred, but fails to see or to speak out on racist policies and so allows racial inequality to persevere. An anti-racist confronts power and policies that keep racial inequities in place and works to resolve them.

With this as an introduction, Kendi proceeds to define modern racism in its various forms. Biological racism maintains the false belief that differences in biology between races create a hierarchy of values. Ethnic racism is directed toward various racialized ethnic groups. Bodily racism posits that black bodies are more animal-like and violent. Cultural racism sets a White cultural standard for people of all races.

Growing up, Kendi even found racism in his family and community. He saw behavioral racism holding the behavior of individuals as a marker for the behavior of an entire group and colorism placing a premium on lighter shades of brown skin. And there was class racism, which ascribes violent or criminal behaviors of certain of members of the Black underclass to all poor Blacks, if not Black people in general.

The heart of Kendi’s book is his brilliant exposition of the roots of American racism, which he claims was birthed with its conjoined twin, capitalism, at the start of the trans-Atlantic slave trade in 1540. Slavery required the devaluation and commodification of Black Africans. Devaluation required scientific and religious “proof” of the inferiority of Blacks as a justification for the elevation of whites. Racist policies developed by capitalism required racist theories, which gave birth to racist ideas. While racist ideas may play out on our streets, they are but the outer manifestation of racist policies enacted by governments for the benefit of the powerful elite. Says Kendi, “The history of racist ideas is the history of powerful policy makers creating racist policies out of self-interest then producing racist ideas to defend and rationalize the inequitable effects of their policies, while everyday people consume those racist ideas, which in turn sparks ignorance and fear.”

“The history of racist ideas is the history of powerful policy makers creating racist policies out of self-interest then producing racist ideas to defend and rationalize the inequitable effects of their policies, while everyday people consume those racist ideas, which in turn sparks ignorance and fear.” — Ibram X. Kendi

Exposing historical attempts to counteract racism, Kendi examines the concepts of assimilationism and moral suasion whose roots extend back to the early abolitionists.

Proclaimed by William Lloyd Garrison, Booker T. Washington, W.E.B Dubois, and Martin Luther King in their times, and numerous Black mothers in all time, assimilationism and moral suasion hold that the key to racial acceptance and racial equality comes through exemplary behavior and educational or artistic achievement on the part of Black Americans.

In time, proponents of the effectiveness of these tactics in eliminating racism came to believe otherwise. In 1876, Garrison admitted, “Expediency on selfish grounds, and not right with reference to the claims of our common humanity, has controlled our action.” Nearly a century later, Dr. King noted, “’We’ve had it wrong and mixed up in our country, and this has led Negro Americans in the past to seek their goals through love and moral suasion devoid of power.”

The problem with assimilationism and moral suasion, in Kendi’s mind, is that they do not ultimately change racist ideas. He says, “Racist policy makers drum up fears of antiracist policies through racist ideas. They know that if antiracist policies are implemented, the fears they circulated will never come to pass.” Witness the tortured history of Obamacare. Or the reactionary fear-mongering following the recent call to restructure policing. Tracing the failure to resolve racism from the early abolitionists through Dubois to King, Kendi says, “The failed solution to racism is the result of failed racial ideology. The misconception of racism as a social construct or a race problem rooted in ignorance and hate as opposed to powerful self-interest has produced failed solutions.”

Only antiracist policies can counteract racism, and an activist is one who realizes it is necessary to change racist policies in order to combat racism. If an action doesn’t lead to policy change, the agent of the action is not an activist. Therefore, according to Kendi, changing minds is not activism, and critiquing racism is not activism. Marching against racism is not activism unless the changing awareness changes votes and ultimately policies. The goals of activism are political power and policy change. In a word, it is more important to change policy than to change minds.

Similarly, one who loudly denies any racist thoughts is still a racist if they support racist policies. Indeed, Kendi scorns those who would say, “I’m not a racist,” or “I am race-neutral” or “I am post-racial” or “I am color blind,” or “There is only one race, the human race,” or “Only racists speak about race” while at the same time support or fail to identify and eliminate racist power and policy.

How to Be an Anti-Racist is thoroughly researched (luckily the footnotes appear at the end) and intellectually thick. But it is, after all, an account of a man’s journey as he gains self-awareness and knowledge. And for this reason, it reads well. And this is good, because the lessons he learns and describes to the reader are lessons we, his readers, will want to understand as well.

Richard Bernstein, M.D., is a family physician, practicing in Charlotte until his retirement in 2013. During his active years, he came to see the art of medicine as a communication between two people. The secret of success in the healing encounter was based on the ability to see the other as a person, an equal, to listen fully, and to communicate without pre-judgement. Upon retirement, he joined the staff of Rokeby Museum as a volunteer guide, then as a member of the board of trustees. He embraces the social justice mission of the museum as a continuation of his medical work.

Rokeby Museum

Rokeby Museum