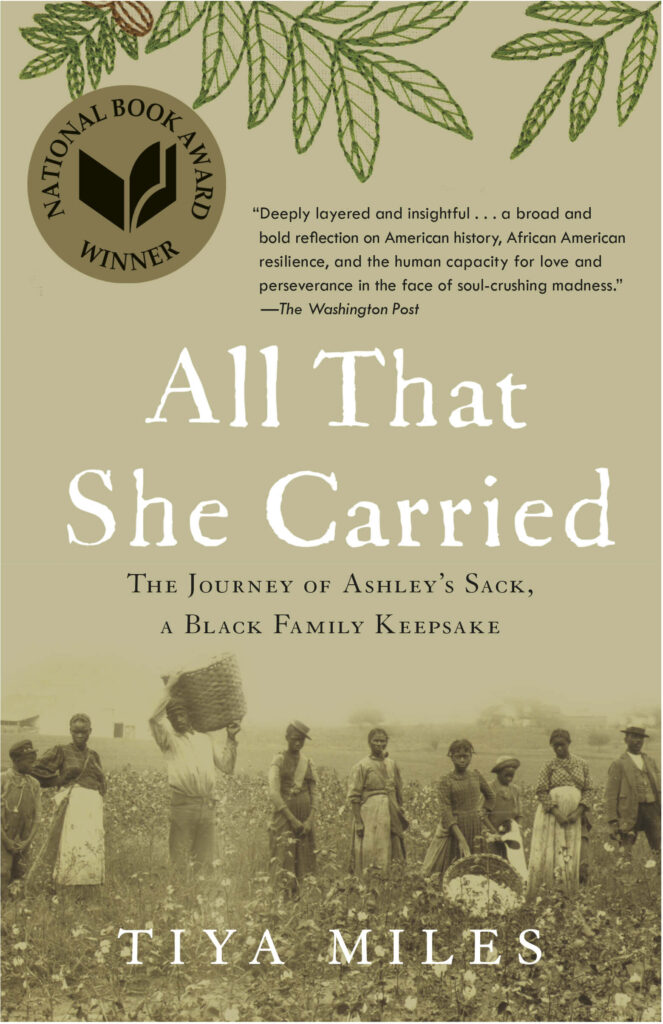

A Reflection on “All That She Carried,” by Tiya Miles

by Joan Gorman, Rokeby Museum

One day last summer I was talking to a visitor about the book, Invention of Wings by Sue Monk Kidd and she asked if I had read, All That She Carried, as that book was the nonfiction version of the time and place Kidd brought to life. As soon as I looked into All That She Carried, I knew I needed to read it and I am very glad that I did.

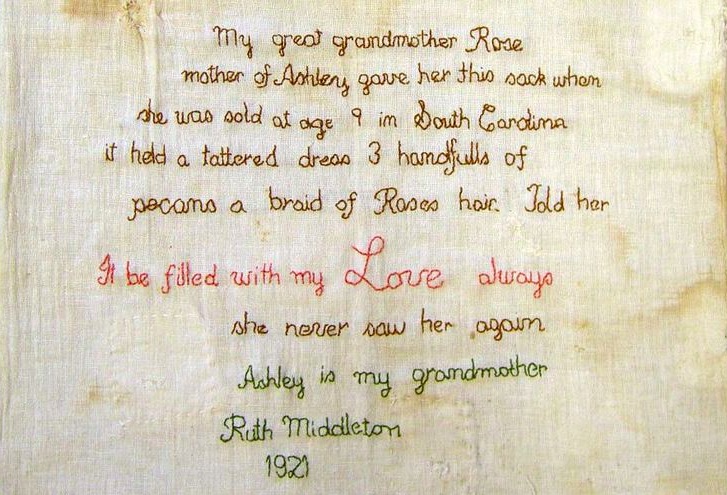

What’s exceptional about Ashley’s sack is that something so intimate was preserved in this way — pressed by a mother into her child’s hands and passed on, so that a descendant who had heard the oral history firsthand could one day decide to inscribe it onto the object itself.

In All That She Carried, Tiya Miles uses a simple textile to tell of the love, trauma, resilience and hope of generations of enslaved people. Rose’s sack, filled with carefully chosen items for her daughter, Ashley, as she was sold away from Rose, and Ruth’s careful stitching of a brief history on the sack several generations later speak volumes about the lives of African-Americans in 19th and early 20th-century America.

ATSC can be looked at on various levels: straight historiography, narrative interpretation of the past, beautifully written creative non-fiction. It is richly layered, exploring both the facts and the emotions of the lives of unfree people in the 19th and early 20th centuries. Miles uses the sack itself, and the items that Rose gave to Ashley to unspool several narrative threads. She draws a connection from the sack to the expanding cotton trade; the lucrative mass crop, Miles says, made for an even more brutal and squalid kind of slavery than the established system of rice cultivation on South Carolina’s marshy coast. The “tattered dress” is a symbol of how the slave system’s reach extended to state laws codifying the kinds of material that enslaved people were permitted to wear. Considering the “3 handfulls of pecans,” Miles writes about food and nutrition; pecans would have been a delicacy in Charleston at the time, prompting her to wonder whether Rose may have been a cook. And the braid provides Miles with a chance to write about hair and what it meant — shorn to punish enslaved women, it was also laden with symbolism, a tie between loved ones separated by distance or death. The trauma of separation — of Ashley from Rose, of daughters from their mothers, of children from their parents — emerges as a central theme of the book, as Miles tries to imagine herself into the lives of the women she writes about. “We must presume that Rose always knew that she would birth a motherless child,” Miles writes.

Much sentimentalism has attached itself to Ashley’s sack and the poetry of Ruth’s embroidered inscription, but the sack was originally an emergency kit, born out of despairing necessity. In slavery, Miles writes, mother love would get entangled in matters of survival, and violent discipline was sometimes seen as a form of rescue: “One formerly enslaved woman painfully recalled how her mother beat her in the same sadistic way that her mother had been abused by whites. ‘She would make me thank her for whipping me.’” Miles traces the lineage as far as she can, up through Ruth Middleton and her daughter, Dorothy, who died in 1988, leaving no heirs. What’s exceptional about Ashley’s sack is that something so intimate was preserved in this way — pressed by a mother into her child’s hands and passed on, so that a descendant who had heard the oral history firsthand could one day decide to inscribe it onto the object itself. The result, as Miles shows, is a fragile object that contains so much, marking “a spot in our national story where great wrongs were committed, deep sufferings were felt, love was sustained against all odds and a vision of survival for future generations persisted.”

Rokeby Museum

Rokeby Museum